Like a grieving lion, God roars each day:

“Woe to My children! On account of their sins I have destroyed My House, set fire to My sanctuary, and exiled them among the nations!” (Berachot 3a)

If the Sages are correct, and God is so deeply distraught about the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash — then why does He not rebuild it?

Emulating God

Before answering this question, we must first examine a more basic issue: how does one go about living a life of holiness? The path to holiness, Rav Kook explained, is based on a single fundamental rule: emulating God. We should strive to compare and equate our conduct to God’s elevated ways. This was King David’s guiding principle: “I have placed God before me at all times” (Psalms 16:8). The phrase “I have placed” (shaviti) may be translated as “I have equated” — “I have equated God to myself at all times.”

The Torah articulates this idea with the command, “You shall follow in His ways“ (Deut. 28:9). As the Sages explained, “Just as God is gracious and compassionate, so you should be gracious and compassionate” (Shabbat 133b). Ethical conduct, positive character traits, and, in fact, all mitzvot and good deeds — they are all based on this principle of emulating God.

But is it possible for the finite to emulate the Infinite? The Sages spoke of “likening the created form to its Creator” (Breishit Rabbah 24:1). Such comparisons require our imaginative faculties. The Hebrew word dimayon means both “comparison” and “imagination.” It is only through our powers of imagination that we are able to envision the application of Divine traits in our lives. From here it is clear that the imagination is a fundamental tool in serving God. And as one advances in holiness, one’s imagination is strengthened and purified.

The various manifestations of a life of holiness — whether a heightened sensitivity to the feelings and property of others, or aesthetic embellishments when performing mitzvot (hiddur mitzvah) — are all expressions of serving God through one’s imaginative powers. Such conduct reflects the refinement of one’s soul and the richness of one’s imagination.

The Nation’s Powers of Imagination

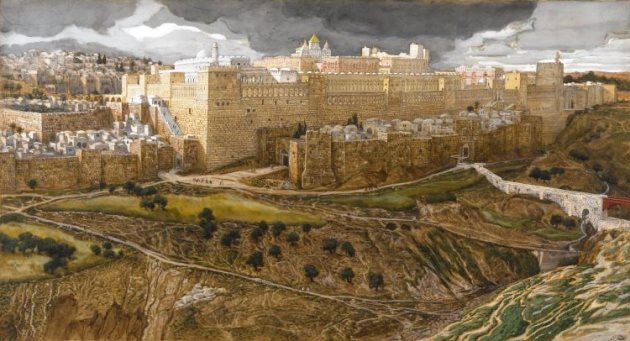

The same principle holds true for the nation as a whole. The awe-inspiring splendor of the Beit HaMikdash, the majestic nobility of the priestly garments, the sanctity and purity of the Temple service — all of these presuppose the importance of a strong and robust imagination. The Sages referred to the Beit HaMikdash as “the Beauty of the universe” to highlight the Temple’s primary function in engaging the aesthetic and imaginative faculties.

Our imaginative powers fulfill their ultimate purpose when they serve as an instrument for enlightenment. In its highest levels, this enlightenment manifests itself as prophetic inspiration and, on the collective level, God’s Divine Presence in Israel.

However, proper use of the imagination requires mental and practical preparation. One cannot attain a richness of God-directed imagination while suffering from ignorance and unrefined character traits. Only wise and virtuous individuals, Maimonides asserted, can attain prophecy (Fundamentals of Torah 7:1). And on the national level, only when the Jewish collective has attained an appropriate ethical and spiritual level will it be possible to restore the Beit HaMikdash. The focal point of Divine beauty in the world requires prerequisite levels of both cognitive and practical holiness.

But while the nation may not be ready for the actual rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash, we still feel the soul’s demand for this lofty spiritual splendor. The soul cries out for its powers of imagination to be cleansed and elevated, purified and enriched. These cries of anguish, this profound sense of loss, may be heard in the terrible roars of Divine grief: “I have destroyed My House, set fire to My sanctuary, and exiled My children among the nations!”

(Silver from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Orot HaKodesh vol. III, pp. 199-200)