Despite his prominence as the chief judge in Babylonia and head of the famed yeshiva of Nehardea, Rav Nachman came under attack from Rabbi Ammi of Tiberius. Or more accurately — Rav Nachman was attacked precisely due to his rabbinical prominence.

On two occasions, Rav Nachman instructed his servant to follow the accepted lenient opinion in Halakhah. The first concerned hatmanah — insulating food on Shabbat. The scholar requested that his food be insulated on Shabbat to keep it cold. This is in accordance with the accepted ruling that hatmanah is only prohibited when keeping food hot.

The second incident took place on a weekday, when Rav Nachman requested that a non-Jewish chef boil him some hot water to drink. The accepted opinion is that Bishul Akum (the rabbinic prohibition to eat foods cooked by non-Jews) does not apply to foods which may be eaten also uncooked, such as water (Shabbat 51a).

So why did Rabbi Ammi object?

Two Models of Personal Example

While we learn from great scholars through their lectures and classes, an even more powerful method is by way of personal example. There are, however, two different models for the way a scholar serves as an example and influences others. These two models are often contradictory. Acting according to one paradigm will frequently be misleading or incorrect in terms of the second.

The first model is for the rabbi to be seen as a practical example of normative Halakhah. People are drawn to the scholar’s nobility of character and great esteem. They see him literally as a living Torah. All of his actions are precisely measured by the Torah’s standards of holiness and Halakhah. People scrutinize his conduct in order to emulate his lifestyle of Torah and mitzvot.

In this situation, the scholar should take care to always follow accepted Halachic rulings. Then it will be clear that his actions are Torah practices applicable to all. If he were to publicly take on special acts of piety, others could no longer learn from him.

This principle is true even if the scholar is naturally drawn to higher religious observance beyond the Halachic norm — middat hassidut — due to deep inner aspirations to be close to God. Nonetheless, he must subdue this desire, so that the people will know that his actions are relevant for all to emulate and follow.

There is, however, a second model of spiritual influence. This is an inspirational influence, when the people see a great scholar as a giant of spirit and intellect. His breadth of knowledge and depth of piety is clearly on a plane far beyond the common man. The people recognize this distance and revere the saintly scholar. His punctilious observance of mitzvoth, even in the smallest details, is clearly not a lifestyle to be emulated, but an inspiring expression of a sublime love of God and Torah.

In this model of influence, it is proper for the scholar to act according to middat hassidut, observing extra stringencies when fulfilling mitzvot, consistent with his exceptional spiritual stature.

Guard against Extremism

The two areas in which Rav Nachman followed the accepted lenient opinion — the laws of Shabbat and Bishul Akum — relate to two fundamental themes in Judaism. Shabbat is an expression of Israel’s spiritual greatness. The Sabbath is “a sign between Me and you” (Ex. 31:13). And the laws of Bishul Akum are designed to emphasize the distinction of the Jewish people, so that the people will be aware and guard over the lofty segulah nature of Israel.

In both of these areas – the greatness of Israel and its separation from the nations — a zealous, unbalanced individual could distort the Torah’s intent, adding extraneous, disturbing, even xenophobic elements. It is necessary to prevent such excesses with qualifying parameters in order to maintain the proper balance. This is rooted in the Torah’s command,

“Carefully observe everything that I am commanding you. Do not add to it and do not subtract from it.” (Deut. 13:1)

For this reason, Rabbi Nachman publicly ordered that his cold food be insulated on Shabbat, limiting the extent of the Sabbath rest. And he requested that a non-Jew heat up his water, so that the divide between Jew and non-Jew not be exaggerated.

But the perfected individual — who fully grasps the wisdom and intent of the Torah — does not need such restrictions. There is no limit to the heights of elevated thought. Going beyond the norms of Halakhah and observing middat hassidut is thus appropriate — and even expected, as Rabbi Ammi forcefully noted — for a great scholar.

(Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. IV, pp. 13-14, on Shabbat 51a)

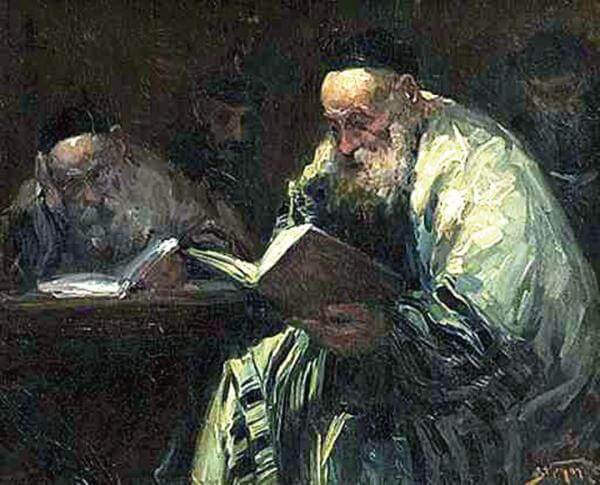

Illustration image: ‘Talmud readers’ (Adolf Behrman, 1876–1942)