Surprisingly, the Torah never spells out exactly where the Temple is to be built. Rather we are instructed to build the Beit HaMikdash “in the place that God will choose”:

“Only to the place that the Eternal your God will choose from all your tribes to set His Name — there you shall seek His dwelling place, and go there.” (Deut. 12:5)

Where is this place “that God will choose”? What does it mean that we should “seek out His dwelling place”?

The Hidden Location

The Sages explained that the Torah is commanding us, under the guidance of a prophet, to discover where the Beit HaMikdash should be built. King David undertook the search for this holy site with the help of the prophet Samuel.

Why didn’t the Torah explicitly state the location where to build the Temple? Moses certainly knew that the Akeidah took place on Mount Moriah in Jerusalem, and he knew that Abraham had prophesied that this would be the site of the Beit HaMikdash. 1

Maimonides (Guide to the Perplexed III: 45) suggested that Moses wisely chose not to mention Jerusalem explicitly. Had he done so, the non-Jewish nations would have realized Jerusalem’s paramount importance to the Jewish people and would have fought fiercely to prevent it from falling into Israel’s hands.

Even worse, knowledge of Jerusalem’s significance could have led to infighting among the tribes. Each tribe would want the Beit HaMikdash to be located in its territory. The result could have been an ugly conflict, similar to Korach’s rebellion against Aaron’s appointment to the position of High Priest. Maimonides reasoned that this is why the Torah commands that a king be appointed before building the Beit HaMikdash. This way the Temple’s location would be determined by a strong central government, thus avoiding inter-tribal conflict and rivalry.

"Between His Shoulders"

In any case, David did not know where the Beit HaMikdash was to be built. According to the Talmud (Zevachim 54b), his initial choice fell on Ein Eitam, a spring located to the south of Jerusalem. Ein Eitam appeared to be an obvious choice since it is the highest point in the entire region. This corresponds to the Torah’s description that

“You shall rise and ascend to the place that the Eternal your God will choose” (Deut.17:8).

However, David subsequently considered a second verse that alludes to the Temple’s location. At the end of his life, Moses described the place of God’s Divine Presence as “dwelling between his shoulders” (Deut. 33:12). What does this mean?

This allegory suggests that the Temple’s location was not meant to be at the highest point, but a little below it, just as the shoulders are below the head. Accordingly, David decided that Jerusalem, located at a lower altitude than Ein Eitam, was the site where the Beit HaMikdash was meant to be built.

Doeg, head of the High Court, disagreed with David. He supported the original choice of Ein Eitam as the place to build the Temple. The Sages noted that Doeg’s jealousy of David was due to the latter’s success in discovering the Temple’s true location.

The story of David’s search for the site of the Beit HaMikdash is alluded to in one of David’s “Songs of Ascent.” Psalm 132 opens with a plea: “Remember David for all his trouble” (Ps. 132:1). What was this trying labor that David felt was a special merit, a significant life achievement for which he wanted to be remembered?

The psalm continues by recounting David’s relentless efforts to locate the place of the Temple. David vowed:

“I will not enter the tent of my house, nor will I go up to the bed that was spread for me. I will not give sleep to my eyes, nor rest to my eyelids — until I find God’s place, the dwellings of the Mighty One of Jacob.” (Ps. 132: 3-5)

David and Doeg

What was the crux of the dispute between David and Doeg? Doeg reasoned that the most suitable site for the Temple is the highest point in Jerusalem, reflecting his belief that the spiritual greatness of the Temple should only be accessible to the select few, those who are able to truly grasp the purest levels of enlightenment — the kohanim and the spiritual elite.

David, on the other hand, understood that the Temple and its holiness need to be the inheritance of the entire people of Israel. The kohanim are not privy to special knowledge; they are merely agents who influence and uplift the people with the Temple’s holiness. The entire nation of Israel is described as a “kingdom of priests” (Ex. 19:6).

The Waters of Ein Eitam

Even though Ein Eitam was never sanctified, it still retained a special connection to the Beit HaMikdash, as its springs supplied water for the Beit HaMikdash. The Talmud relates that on Yom Kippur, the High Priest would immerse himself in a mikveh on the roof of the Beit HaParvah chamber in the Temple complex. In order for the water to reach this roof, which was 23 cubits higher than the ground floor of the Temple courtyard, water was diverted from the Ein Eitam springs, which were also located at this altitude.

Rav Kook explained that there exists a special connection between Ein Eitam and the High Priest’s purification on Yom Kippur. While the Beit HaMikdash itself needs to be accessible to all, the purification of the High Priest must emanate from the highest possible source. Yom Kippur’s unique purity and power of atonement originate in the loftiest realms, corresponding to the elevated springs of Ein Eitam.

(Sapphire from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Shemu'ot HaRe’iyah (Beha’alotecha), quoted in Peninei HaRe’iyah, pp. 273-274,350-351. Shemonah Kevatzim I:745)

1 After the Akeidah, it says: “Abraham named that place, ‘God will see'; as it is said to this day: ‘On the mountain, God will be seen'” (Gen. 22:14).

Rashi explains: “God will choose and see for Himself this place, to cause His Divine Presence to dwell there and for sacrifices to be offered here”

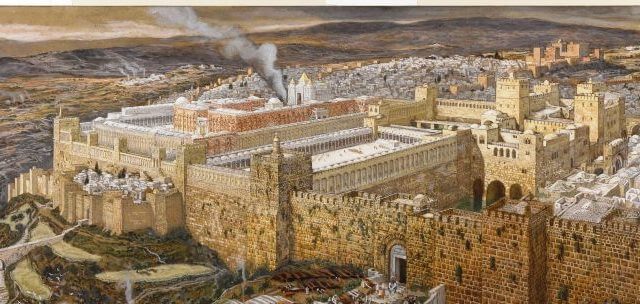

Illustration image: ‘Reconstruction of the Temple of Herod Southeast Corner’ (James Tissot, between 1886-1894)