Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying: This is how you should bless the Israelites... (Num. 6:23)

Rav Kook’s duties as Chief Rabbi of Jaffa and the surrounding settlements were demanding and complex. In order to rest from the long hours and the pressures of the position, Rav Kook would go on vacation in the late summer, staying in the agricultural settlement of Rehovot during the peak of the grape harvest season.1

In a letter written in 1910, Rav Kook expressed his joy at seeing the moshavah grow and flourish:

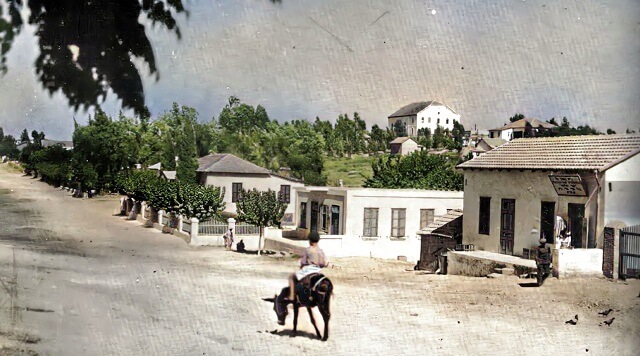

I am currently residing in Rehovot, may it flourish and thrive. I am completely enthralled by Godly hopes and consolations, as I see with my own eyes the development of our precious land. Once desolate, it is now cultivated by the hands of our brethren who were scattered throughout the Exile and are gradually returning. My heart rejoices at the sight of peaceful dwellings, delightful vineyards, the beauty of the grape, fig, and pomegranate trees in the fields of our people, in the place of [Zion], the wellspring of our lives. (Letters vol. I, p. 359)

However, even in Rehovot, it was not a simple matter for Rav Kook to rest. The local residents were thrilled to host the revered scholar. They sought out his advice, not only on Halakhic matters, but also on local administrative issues — municipal tax collection, paving local roads, and so forth. And if a Torah subject was broached, Rav Kook became an overflowing wellspring of knowledge and creativity; he would often expound on a topic for hours.

While in Rehovot, Rav Kook would stay in the modest home of the Lipkovitz family. Abraham Isaac Lipkovitz, who worked in construction and agriculture, had studied Torah in European yeshivot before making aliyah with his family at age 18. He took upon himself to facilitate his esteemed guest’s rest and recuperation. Lipkovitz took this duty most seriously and formulated an appropriate plan. He zealously watched over the Rav’s meals and sleep, adamantly preventing anyone from disturbing him while he slept, no matter what the occasion.

But it quickly became apparent that in the Lipkovitz home and in the synagogue, where Rav Kook was constantly badgered with queries and solicitations, the rabbi could not properly rest.

The Lipkovitz’s owned a vineyard, one that produced some of the choicest grapes in the country. Lipkovitz built a simple hut inside the vineyard for Rav Kook’s personal use. Each day, he would lead Rav Kook to the vineyard on a donkey. And for two hours, Rav Kook would rest in the hut.

Lipkovitz probably assumed that the rabbi spent this quiet time resting, eating grapes, and reading light material. In fact, Rav Kook’s mind was far away from Rehovot and its bountiful vineyards. His thoughts soared to the rarified heights of Lithuanian Torah scholarship. He utilized those precious hours of peace and quiet to engage in serious research, producing an erudite commentary to the glosses of the famed Rabbi Elijah, the Gaon of Vilna, on the Shulchan Aruch. This scholarly work, Be'er Eliyahu (Elijah’s Well), elucidates the Gaon’s terse hints and novel ideas on Halakhah and Talmud.

Many years later, during his final illness, Rav Kook described his feeling of profound privilege when working on this project. “When I was writing Be'er Eliyahu, I felt as if I was standing in the very presence of the Gaon of Vilna. It was as if I was presenting to him the books — the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, the works of Maimonides and the other Rishonim [medieval rabbinic authorities].” Rav Kook’s eyes flowed with tears. “I thank God for the great honor of serving our master, the Gaon, to a small degree.”

Visitors would frequently arrive from Jaffa or Jerusalem to consult with Rav Kook. They were allowed to accompany him on the trip to the vineyard. But once they reached the vineyard, they were barred from entering. Lipkovitz gave strict orders to his Arab watchman not to allow any visitors to disturb the rabbi.

Rav Kook’s Blessing

Lipkovitz was overjoyed with the privilege of serving Rav Kook. He also had a modest request of the rabbi, a request which took him time until he succeeded in bringing it up with his esteemed guest. Lipkovitz related:

Rav Kook stayed at my house, and I very much wanted to receive a blessing from him. But the Rav was always absorbed in his Torah studies, or he had visitors, and I dared not interrupt.One day I noticed that the Rav had raised his eyes from the Torah text he was studying. At the time I was holding some chickens in my hands. I immediately released the chickens and dashed to the Rav in order to present my request.

“You need a blessing?” the Rav replied in surprise. “After all, you merited to ascend to the Land of Israel and live in the Holy Land with financial security.”

The Rav paused for a moment. “Nonetheless, I am a kohen; and it is a mitzvah for me to bless the Jewish people at all times.”

Rav Kook then blessed me that I would merit a long life — arichut yamim — until the time of the Redemption.

“From that time on,” Lipkovitz remarked, “I lived in tranquility, placing my faith in the scholar’s blessing.”

After the Six-Day War in 1967, when the Old City of Jerusalem was liberated and the borders of Israel were expanded, Lipkovitz began to worry. Perhaps the Rav’s blessing has already been fulfilled? Perhaps his hour had arrived?

In fact, Abraham Isaac Lipkovitz lived many more years. He finally passed away at the ripe old age of 108. Until his death, he was known as zekan hayishuv, “the community elder.” Over the years, when people asked him how he had merited such a long life, he would reply with simplicity, “Why, I have a blessing from Rav Kook!”

(Stories from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Chayei HaRe’iyah, pp. 332-337. Shivchei HaRe’iyah, pp. 91-95)

1 During his stay in England during World War I, Rav Kook traveled to the spa town of Harrogate, where his doctor insisted he spend time each day touring its famous parks and gardens. In an attempt to raise the rabbi’s spirits, his assistant, Rabbi Glitzenstein, pointed out the park’s beautiful views and landscapes. “But it is not Rehovot,” Rav Kook responded sadly. “In Rehovot’s holy and beloved vistas, I could take pleasure. But what connection do I have to these foreign lands, where a foreign spirit prevails?”