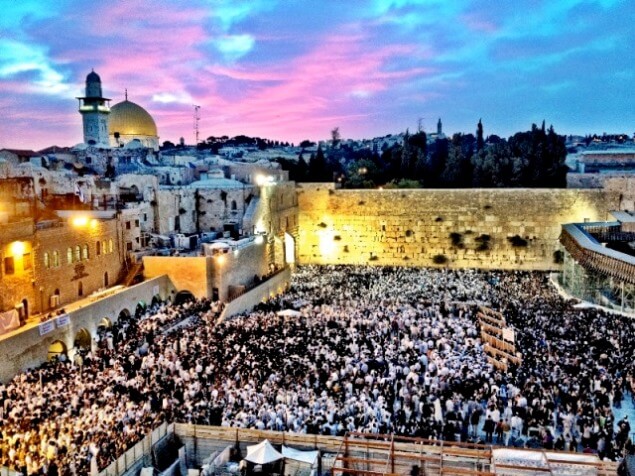

What is the significance of the Kotel? Why do Jews gather from around the world to pour out their hearts facing this ancient stone wall?

In 1937, Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook published an article entitled, “Behind our Wall.” The rabbi chose a title that evokes God’s constant presence at the Kotel:

“Behold, [my Beloved] is standing behind our wall, looking from the windows, peering from the lattices.” (Song of Songs 2:9)

Rav Tzvi Yehudah objected to the term “Wailing Wall.” He felt that this is a superficial description of the Kotel as a place of mourning and inconsolable loss. Even worse, this name suggests the helplessness of a weak and stateless nation.

More appropriate, he felt, is the name Kotel HaMa’aravi, the “Western Wall.” This term describes the Kotel as a holy remnant of the Second Temple complex (and, in fact, the Temple Mount wall which was located closest to the Holy of Holies). It recalls the ancient tradition that “the Shekhinah has never left the Western Wall,” and denotes the Kotel as a symbol of the eternal nature of Israel, despite centuries of exile and persecution. Its unmoving stones are testimony that the Jewish people will return to their land and lofty heritage.

When originally published, the article was mistakenly attributed to Rav Kook. The article was later included in a collection of Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook’s writings called LeNetivot Yisrael. Below is a translation of excerpts from the article, as well as the popular song that it would inspire forty years later.

“Behind our Wall,” by Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook

Secure and invincible with its Divine strength, the Kotel holds its own — throughout the generations of change, transformations and vicissitudes, the horrors and the upheavals, which visited the land and its inhabitants. The Kotel is in them and with them.

Even if the disgrace of ruin conceals its beauty, and signs of destruction are displayed prominently over it, and clouds of desolation cast shadows over its radiance; even if it is hidden behind a thicket of dark and squalid alleys, as it is shoved aside in the cruelty of its neighbors, surrounding it from all sides, who attempt to invade its borders, to suppress and consume its legacy. Nonetheless, like a stone fortress, it stands guard, unwavering, without allowing its inner dignity to be sullied. It remains pure and exalted in the strength of its very essence...

For it is a remnant of the holy and precious, of the Divine abode. In the wonderful quality of its very existence, it is a witness to world events and millennia of human history.

יש לבבות ויש לבבות. יש לבות אדם, ויש לבות אבנים.

There are hearts and there are hearts. There are human hearts, and there are hearts of stone.

ויש אבנים ויש אבנים. יש אבני דומה, ויש אבנים-לבבות.

There are stones and there are stones. There are silent stones, and there are stones which are hearts.

These stones, remnants of our dwelling on high, “retain their holiness even in desolation” (Megillah 3:3), for “the Shekhinah has never left the Western Wall” (Tanhuma Shemot 10).... These stones are our hearts!

Each of us knows that this wall, for all of its somber simplicity and signs of ruin and exile, is not a “Wailing Wall” for us, as it is called by strangers and foreigners. To us, it is a wealth of life, a hidden treasure of light and strength, safeguarded and secured by our tears.

The healthy Jewish eye does not see in the Kotel a symbol of our nation’s ruin, devastation, and decay. On the contrary, we see the wall, in its hidden strength and resilience, still standing — even after they fell and when they fell — as it rises up and reaches out with Divine strength to eternal redemption.

Yossi Gamzu’s song — “The Kotel”

After the Kotel’s liberation in the Six-Day War, Israeli lyricist Yossi Gamzu composed a song that quickly became an Israeli classic — HaKotel. Gamzu utilized imagery from Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook’s 1937 article. He even dedicated one stanza to Rav Tzvi Yehudah, accurately describing the rabbi’s lofty elation during this historic event, as well as his profound love for the Jewish soldiers who fought in the war.

The Kotel

The Kotel, moss and sadness;

The Kotel, lead and blood.

There are people with a heart of stone;

And there are stones with a human heart.

...

Together with us, facing the Kotel,

Stands an elderly rabbi in prayer.

He said, “Fortunate are we, that we all merited this!”

Then he remembered. “But not everyone.”

He stood with glistening tears.

Alone, among the dozens of soldiers.

He said, “Under your khaki uniforms, in truth,

You are all holy priests and Levites.”

(Stories from the Land of Israel. LeNetivot Yisrael, vol. I, pp. 22-25)