With the Jewish people’s return to the Land of Israel, the question of the Halakhic status of Har HaBayit — the plot of land where the Temple once stood in Jerusalem – became a hot topic. Does it still have the unique sanctity that it acquired when Solomon consecrated the First Temple? Does a person who enters the area of the Temple courtyard (the azarah) while ritually impure (tamei) transgress a serious offence, incurring the penalty of karet?1

Or did the Temple Mount lose its special status after the Temple’s destruction?

This issue was the subject of a major dispute some 900 years ago. Maimonides noted that the status of Har HaBayit is not connected to the question about whether the Land of Israel in general retained its sanctity after the first exile to Babylonia. The sanctity of the place of the Temple is based on a unique source — the Divine Presence in that location – and that, Maimonides argued, has not changed. “The Shekhinah can never be nullified.”2

Maimonides buttressed his position by quoting the Mishnah in Megillah 3:4: “Even when [your sanctuaries] are in ruins, their holiness remains.

However, Maimonides’ famous adversary, Rabbi Abraham ben David (Ra’avad), disagreed vehemently. This ruling, Ra’avad wrote, is Maimonides’ own opinion; it is not based on the rulings of the Talmud. After the Temple’s destruction, the Temple Mount no longer retains its special sanctity. A ritually-impure individual who enters the place of the Temple courtyard in our days does not incur the penalty of karet.

Rav Kook noted that even Ra’avad agrees that it is forbidden nowadays to enter the Temple area while impure. It is not, however, the serious offence that it was when the Temple stood.3

What is the source of this disagreement?

Like a Tallit or Like Tefillin?

In Halakhah there are two paradigms for physical objects that contain holiness. The lower level is called tashmish mitzvah. These are objects like a garment used for a Tallit, a ram’s horn used for a Shofar, or a palm branch used for a Lulav. All of these objects must be treated respectfully when they are used for a mitzvah. But afterwards, they may be freely disposed of (covered and then thrown away). Their holiness is only in force when they are a vehicle for a mitzvah. The holiness of a tashmish mitzvah is out of respect for the mitzvah that was performed with it.4

But there is a second, higher level, called tashmish kedushah. These are objects which have an intrinsic holiness, as they are vessels for holy writings. This category includes Tefillin, Sifrei Torah, and Mezuzot. It also includes articles that protect them, such as covers for Sifrei Torah and Tefillin boxes. Unlike tashmishei mitzvah, these objects may not be simply disposed of when no longer used. They must be set aside (genizah) and subsequently buried.

For Ra’avad, the land under the Temple falls under the category of tashmish mitzvah. It facilitated the many mitzvot that were performed in the Temple. Without the Temple, however, the area no longer retained its special kedushah. It became like an old Tallit, no longer used to bear tzitzit.

Maimonides, on the other hand, categorized the Temple Mount as a tashmish kedushah. This area was the location of the unique holiness of the Shekhinah, an eternal holiness. Like a leather box that once contained Tefillin scrolls, even without the Temple this area retains its special level of kedushah.

“Sanctified by My Honor”

All this, Rav Kook suggested, boils down to how to interpret the words “וְנִקְדַּשׁ בִּכְבֹדִי” — "sanctified by My Honor” (Exod. 29:43). The Torah describes the holiness of the Tabernacle — and later the Temple:

There I will meet with the Israelites, and [that place] will be sanctified by My Honor (Kevodi).

What does the word Kevodi mean?

We could interpret Kevodi as referring to the honor (kavod) and reverence that we give this special place. The Tabernacle and Temple were deserving of special respect (like the mitzvah of mora Mikdash). But without the Temple functioning, it no longer retains its former kedushah — like the opinion of Ra’avad.

On the other hand, the word Kevodi could be understood as referring to Kevod Hashem — the Shekhinah, God’s Divine Presence in the Temple (see Rashi ad loc.). As the verse begins, “There I will meet with the Israelites.” This would indicate an intrinsic holiness which is never lost — like the opinion of Maimonides.

In his Halakhic work Mishpat Kohen, Rav Kook explained our relationship to the place where the Temple once stood:

The Temple is the place of revelation of the Shekhinah, the place of our encounter with God. We do not mention God’s holy Name outside the Temple due to the profound holiness of His Name; so, too, we do not ascend the Mount nor approach the Holy until we will be qualified to do so. And just as we draw closer to God by recognizing the magnitude of our inability to grasp Him, so too, we draw closer to the Mount precisely by distancing ourselves from it, in our awareness of its great holiness. (p. 204)

(Adapted from Iggerot HaRe’iyah vol. III, letter 926)

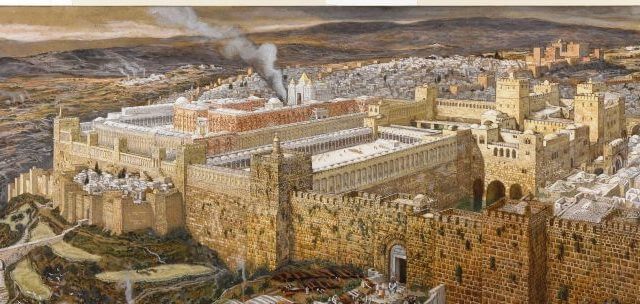

Illustration image: James Tissot, ‘Reconstruction of the Temple of Herod Southeast Corner’ (between 1886 and 1894)

1 Karet, literally "cutting off,” is a spiritual punishment for serious transgressions. Karet can mean premature death, dying without children, or a spiritual severing of the soul’s connection with God after death.

2 Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Temple, 6:16

3 What would Ra’avad do with the Mishnah in Megillah that Maimonides quoted? He could explain that this homiletic interpretation is only an asmakhta, and reflects a prohibition of the Sages. Or the Mishnah could be referring to other laws, such as the mitzvah of mora Mikdash — the obligation to show respect and reverence to the Temple area by not entering the Temple Mount with one’s staff, shoes, or money belt; by not sitting in the Temple courtyard; and so on. (See Berakhot 54a; Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Temple, chapter 7).

We might have expected a reversal of positions — that Ra’avad would argue for its eternal sanctity, given that Ra’avad was a Kabbalist, unlike Maimonides the rationalist. Especially considering that Ra’avad explicitly notes that his position is informed by inspired wisdom — “God confides in those who fear Him” (Psalms 25:14).

In fact, it could well be that Ra’avad’s opinion is based on his understanding of the distinct spiritual status of each Temple. Solomon foresaw the higher spiritual state of the Third Temple, so he intentionally limited the sanctity of the First Temple. He conditioned its sanctity to expire with the Temple’s destruction, in order to enable the future Temple to be established on a higher state of kedushah.

4 This is the explanation of Nachmanides, quoted by the Ran in Megillah, chapter 3.