The Talmud tells the story of a student who deposited a sum of money with a man who was ostensibly religious. This was a man who was careful to wear tefillin every day. When the student came to collect his money, he was shocked to hear the man deny ever having received it.

“I did not deposit the money with you,” the young man responded bitterly.

“I deposited it with the tefillin on your head!”

Was this merely an expression of the student’s disgust that a supposedly religious person would act this way? Or is there a deeper connection between tefillin and moral integrity?

A Clean Body

The Sages taught that one should follow the example of Elisha Ba’al Kenafayim (“the Master of Wings”). Elisha was always careful to only wear tefillin with a guf naki, when his body was clean. Tefillin are holy objects; wearing them requires a strict standard of hygiene and control over one’s bodily functions.

Who was this Elisha, the “Master of Wings”?

The Roman government once proclaimed a decree against Israel: anyone laying tefillin will be executed by having his brains pierced through. Despite the danger, Elisha put on tefillin and went out to the marketplace.

Unfortunately, a Roman official spotted Elisha in the market wearing tefillin. Elisha fled, and the official chased after him. When Elisha realized that he would soon be caught, he removed the tefillin from his head and hid them inside his hand.

The officer demanded, “What is that in your hand?”

Elisha replied, “The wings of a dove.”

Elisha then opened up his hand – and inside were the wings of a dove. From then on, he was called Elisha, the Master of Wings.

What is the significance of these dove wings? And how does the story of Elisha corroborate the requirement that tefillin be worn with a clean body?

Two Levels of Morality

The Torah calls tefillin an oht, a sign. They are a sign of the unique covenant between God and Israel. By wearing tefillin, we testify to the Jewish people’s mission as “a kingdom of kohanim and a holy nation.” Due to this special mission, the moral path of Israel is beyond that which is expected of other peoples. “God did this for no other nation; they do not know His laws” (Psalms 147:20).

All of humanity is expected to comply with the Noahide Code,2 the foundation of natural morality. All peoples should aspire to a basic integrity, a love of justice and a hatred of evil. This standard of conduct does not presuppose great spiritual aspirations. It is sufficient that one’s character has not been corrupted by the rapacious cruelty of beasts of prey. This basic level of moral purity, when one’s natural inclinations have not been soiled by greed and lust, may be called guf naki.

Those who wish to ascend God’s mountain — those who aspire to a higher ethical level, as represented by the lofty holiness of tefillin — must first have a “clean body.” They must acquire the fundamental level of moral rectitude, and not have lost their innate purity through ignoble traits and dark deeds.

Only after acquiring the level of natural morality may one ascend the ethical ideal that corresponds to the unique holiness of Israel. Then one may proudly wear tefillin, and “God’s name will be called upon you” (Deut. 28:10).

This is the significance of the dove wings that appeared in Elisha’s hand. Wings enable one to ascend, to scale the mountain of elevated morality, uplifting the soul that has already acquired the basic level of morality.

One cannot attain this higher level while one’s heart is impure and drawn to injustice. One must first have a “clean body,” a basic level of decency and integrity.

Wings to Soar

What does all this have to do with Elisha’s extraordinary dedication to the mitzvah of tefillin?

The ability to remain firm in our beliefs, even in the face of hardship and danger, indicates that we have fully internalized the level of holiness to which our soul aspires. According to the degree by which we have assimilated this level, we will find within ourselves the inner strength to withstand the challenges of the turbulent sea that rages around us.

To be tightly bound to the holiness of tefillin, one must first acquire the preliminary level of natural morality, a guf naki. And yet one must feel that this level, with all of its innate purity, cannot satisfy the soul’s aspirations to scale the lofty heights of the Torah’s elevated morality.

One who is a Master of Tefillin will also be a Master of Wings. His physical nature will not be able to confine his spirit earthbound. He will find inner resources of strength and dedication, even in an hour of trial. Elisha, in his brave stand against a cruel and evil regime, was worthy of the title “Master of Wings.” The dove wings that appeared in his hand testified to the purity of his body and the loftiness of his soul.

(The Splendor of Tefillin. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. III sec. 1 on Shabbat 49a)

2 The Noahide Code consists of seven basic laws given to all of humanity after the Flood. The code prohibits idolatry, murder, theft, forbidden relations, blasphemy, and eating the meat of living animals, and it mandates the establishment of a system of courts.

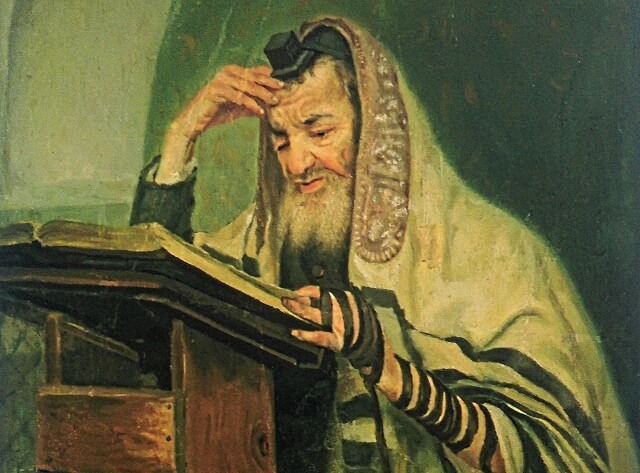

Illustration image: ‘Morning prayer’ (Jacob Kruger, 1897)