by Joshua Hoffman

(Orot, vol. 1 5751/1991 a)

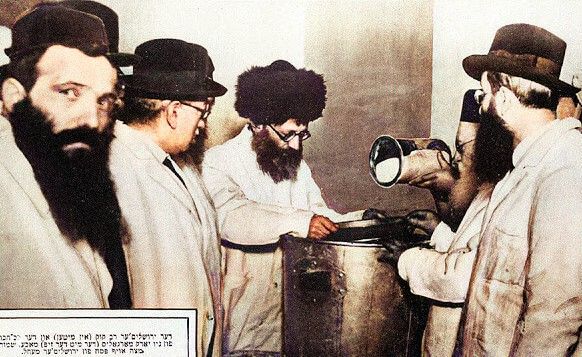

The Central Relief Committee (CRC) Emergency Campaign

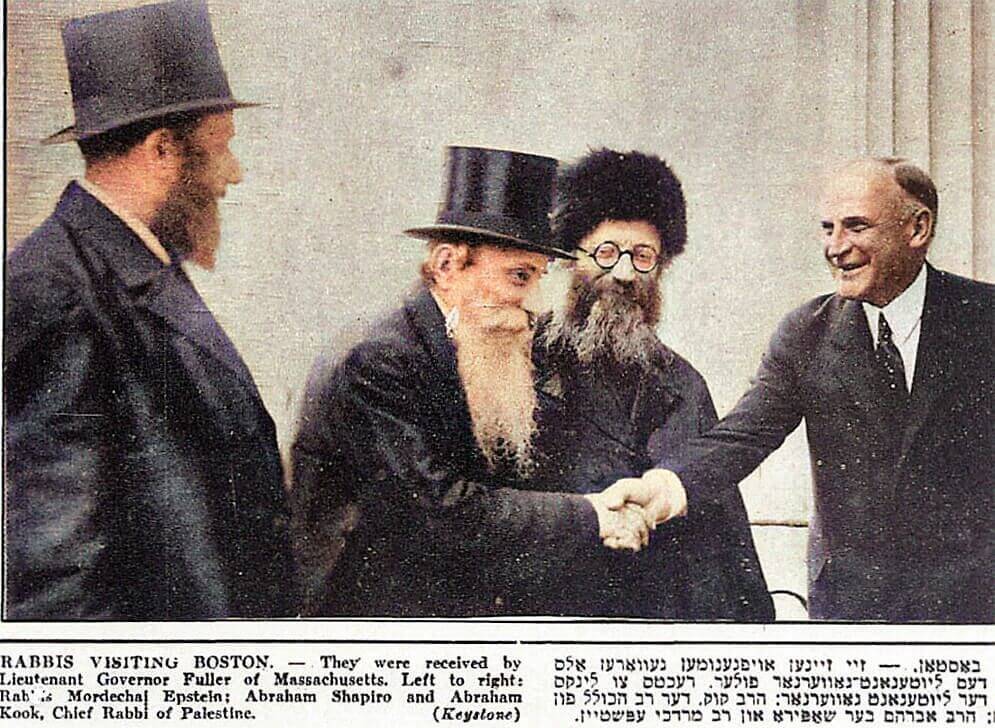

In March, 1924, Rav Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook came to America as part of a rabbinic delegation whose purpose was to raise funds for Torah institutions in Eretz Yisrael and Europe. The other members of the delegation were, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, head of the Slabodka Yeshiva, and Rav Avraham Dov Baer Kahana Shapiro, the Rav of Kovno (Kaunas) and president of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim of Lithuania. The three rabbis were brought to America by the Central Committee for the Relief of Jews Suffering Through the War, better known as the Central Relief Committee (CRC).

The Central Relief Committee was founded by leaders of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim, the Union of American Orthodox Congregations, and other Orthodox Jews on October 8, 1914, to raise funds for the assistance of the masses of Jews overseas left homeless and impoverished as a result of the upheavals of World War I. On October 25, 1914, the American Jewish Relief Committee was formed by a more heterogeneous religious group.1 The committees decided to pool the funds they collected into the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), formed on November 27, 1914 to act as a disbursing agency. In mid-1915, the labor groups formed the People’s Relief Committee, which also joined the JDC.

In 1922, the JDC decided that each of its three committees take over the obligation of supporting those overseas educational institutions which they aligned with. Accordingly, the CRC supported all the Orthodox institutions previously funded by the JDC.2 Many European yeshivot and talmud torahs had been exiled during World War I and were now in the process of returning to their original homes, some of which had to be rebuilt, or of reopening at new locations, and the cost involved in these operations was tremendous. Funds were also needed to support the students attending these institutions. By 1923, the CRC realized that to continue functioning, it must launch an emergency fund-raising campaign, and for this purpose, began plans, late that year, to bring to America a group of the most prestigious rabbis of the time, to help encourage Jews to contribute.3

Rav Kook, being Chief Rabbi of Palestine, was an obvious choice. Because of the many duties which his office demanded, he requested that someone else be found, but the CRC convinced him of the necessity of his participation, and so, in February 1924, after a mass send-off, he sailed for America.4 The major leaders of European Jewry — the Hafetz Hayyim and Rabbi Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski — were unable to come.5 Instead, Rabbis Epstein and Shapiro, both outstanding figures in their own right, were asked to join the delegation.

Arrival in New York City

Rabbi Epstein arrived in New York on January 30, 1924,6 accompanied by Rabbi Ya’akov Lessin, a founder of the Slabodka Kollel, and later the Mashgiah Ruhani (Spiritual Advisor) of the Rabbi Isaac Elhanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) in New York.7 Rabbi Epstein arrived early in order to raise funds for his own yeshiva. He spent part of his time in Chicago, where his brother, Rabbi Ephraim Epstein, was spiritual leader of the Knesset Israel synagogue. Rabbi Shapiro, accompanied by Rabbi Avraham Faivelson, secretary of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim of Lithuania,8 met Rav Kook in Cherbourg, France, from where they sailed together on the S.S. Olympic to America. They arrived in New York on the evening of March 18, 1924.

On the morning of March 19, the two rabbis were greeted by thousands of Jews, among them hundreds of rabbis, singing HaTikvah. This being Rabbi Kook’s first trip to America, his appearance provoked great excitement. When he stepped off the ship, the impression he made was so striking that it led one non-Jewish reporter, not content with giving him the title “Chief Rabbi of Palestine,” to dub him, “the Jewish pope.” He was, however, quickly informed the Jews don’t have such a position.9

The two rabbis were met by Rabbi Epstein, and the three of them were then driven at the head of an automobile procession to City Hall, where they were officially received by Mayor John P. Hylan and other public dignitaries. An enthusiastic reporter wrote that this was probably the greatest honor given a rabbi by a public official since Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel visited London and was greeted by Oliver Cromwell! Mayor Hylan made a short welcoming speech, and presented the rabbis with the “Freedom of the City.”

Rabbi Kook then delivered a message in Hebrew, which was translated by Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein. In his message, he thanked the American People for supporting the Balfour Declaration. He was referring to a resolution passed by both houses of Congress and signed by President Harding in 1922, recognizing the Declaration. Rabbi Kook also told the mayor that the honor being shown the rabbinic delegation was really an expression of honor towards the Jewish People and its Torah, which is the light of the world. This expression of honor, he added, was an indication that America was holding true to its ideals of equality and brotherly love. The mayor then shook hands with Rabbi Kook, who proceeded, to the mayor’s surprise, to converse with him in proper English.

The rabbis were then taken to their quarters at the Hotel Pennsylvania.10 They stayed at that location for a few weeks, and then relocated to a private home on West 76th Street, which Mr. Harry Schiff had put at their disposal. That house was their headquarters for the duration of their stay in America.11

During their eight months in America, the rabbinic delegation visited ten major cities, several smaller ones, and various neighborhoods throughout the metropolitan New York area. The basic pattern of their reception in New York was followed in all the cities they visited. There was a large crowd greeting them on their arrival, followed by an automobile procession to City Hall, where they were received by local officials and given the key to the city. During their stay in the city, the rabbis would visit the local talmud torahs or yeshiva and attend rallies and banquets, where they would speak of the CRC’s relief efforts and appeal for funds. Invariably, Rav Kook received the most attention and generated the most enthusiasm.12

Rav Kook’s predominance in the delegation, despite the tremendous stature of his two colleagues, was partially engineered by the CRC itself. The committee had designated him as the spokesman for the group and the other two rabbis agreed to this move. Simply as a fund-raising tactic, the CRC felt that emphasizing the appearance of Rav Kook, the first chief rabbi of Palestine, in America, would create a greater response and lead to a larger contribution of funds. When the CRC asked prominent public officials including President Coolidge, to send greetings to the rabbinic delegation to be read at major fund-raising events, they pointed out that it was especially important to mention Rav Kook.13 There was a great deal of Jewish pride aroused by the phenomenon of the Chief Rabbi’s visit, and the CRC tried to utilize it to the utmost in the interest of the Torah institutions of Europe and Palestine.

There was, however, more behind Rav Kook’s predominance, beyond the significance of his rabbinical position. His personality and intellect were unique even among such rabbinic giants as Rabbis Shapiro and Epstein, and this was immediately perceived by those who came in contact with him or heard him speak.14 His reputation for demonstrating love and appreciation for all Jews, even those estranged from tradition, was well known. As early as 1912, a writer for the Boston Jewish Advocate had suggested that Rav Kook, then Chief Rabbi of Jaffa, come to Boston to serve as chief rabbi, to replace Rabbi Gavriel Ze'ev (Velvel) Margolis, who had moved to New York in 1911. The writer felt that Rav Kook’s ability to appeal to all segments of Jewry in Palestine, would enable him to unite the various elements of Boston Jewry.15 By 1924, many of Rav Kook’s works had already been published, and he was known as a poet and philosopher who incorporated elements of modern, secular thought into his Jewish world-view, a rare occurrence among Orthodox rabbis of his time.16

The special attention which Rav Kook received in America was highlighted by a reporter for the Jewish Daily Forward, who went to the Hotel Pennsylvania to interview the rabbi. When the reporter approached the information desk in the lobby, he was immediately asked, “Are you here to see the rabbi?” He received the same query from members of the hotel staff on the fifth floor, where the delegation was staying. At their suite, it was Rav Kook who was surrounded by reporters and visitors, although all three rabbis were staying there.17 Rav Kook himself had an ambivalent attitude towards the honor shown him. In a letter to his son, R. Zevi Yehuda, he wrote that he was suffering from afflictions of honor, which involve loss of time from prayer and Torah study.18 In another letter, however, he wrote that the honor shown him by public officials as a representative of the rabbinate, was a positive development, which could be used to advantage by the American Jewish community in the future.19

On April 2, at the Hotel Astor, a reception was held for the rabbinical delegation, officially launching the Torah Fund campaign. All three rabbis addressed the gathering, with Rav Kook being the last speaker. He spoke of Zion and Jerusalem in a manner so deep, noted one observer, that many listeners had a difficult time understanding him. He also noted that one could ascribe to Rav Kook what the sages ascribed to Queen Esther, namely, that he had a special appeal for each group present. Members of Mizrahi, Agudat-Yisrael, Hasidim, Zionists and others, all felt that Rav Kook’s remarks supported their particular philosophy.20 Another reporter wrote that the speech projected an unusual, superhuman love for Eretz Yisrael, one which only Rav Kook, the chief rabbi of the land, could display.21

On April 3, Rav Kook began a series of shi'urim (lectures) at RIETS. The content of the shi'urim was not transcribed, but it was noted that he discussed the nature of court testimony, the laws of Eretz Yisrael, and Jewish culture. One of the concepts he developed was that of the corporate, metaphysical entity of Israel, i.e., its zibbur aspect.22 One commentator was astonished by Rav Kook’s ability to deliver a traditional-style Talmudic lecture, including all the elements of in-depth analysis, in a fluent Hebrew. He then submitted Rav Kook’s shi'ur as an argument for the use of the Ivrit be-Ivrit system in American Hebrew schools!23 Another writer noted the fusion of halakha and aggadah in Rav Kook’s shi'ur, as well as the great love he expressed for Jews, Torah and Eretz Yisrael. Sitting in New York, listening to Rav Kook, he wrote, one felt he had been transported to Jerusalem, because Rav Kook brought Jerusalem with him to New York.24

The White House

On April 15, Rav Kook met with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. Although the President had a meeting with his cabinet that same day, and it wasn’t his usual day for receiving visitors, he considered it a great honor to meet with the chief rabbi of the Holy Land, and therefore broke with his usual custom and granted him an audience.25

At the meeting, Rav Kook thanked the President for his government’s support of the Balfour Declaration, and told him that the return of the Jews to the Holy Land will benefit not only the Jews themselves, but all mankind throughout the world. He quoted the Talmudic sages as saying that no solemn peace can be expected unless the Jews return to the Holy Land, and therefore their return is a blessing for all the nations of the earth. Rav Kook also expressed the gratitude of Jews throughout the world towards the American government for aiding in relief work during the war. He said that America has always shown an example of liberty and freedom to all, as written on the Liberty Bell, and that he hoped that the country will continue to uphold these principles and render its assistance whenever possible. The speech, written in Hebrew, was delivered in English by Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, executive secretary of the CRC. Rav Kook answered “Amen”, and explained that since he wasn’t fluent in English, he had Rabbi Teitelbaum read his message. By answering “Amen”, he indicated that he consented to every word that had been read. The President responded that the American government will be glad to assist Jews whenever possible.26 Before leaving Washington, Rabbis Kook and Teitelbaum held a meeting of local rabbis and community leaders to raise money for the Torah Fund.27

Rav Kook’s remarks to President Coolidge on the universal significance of the Jews’ return to their homeland are typical of remarks he made to public officials throughout his stay in America. As mentioned, he told Mayor Hylan that the Torah is the light of the world. While in Montreal, he told the mayor of that city that “the ultimate return of the Hebrews to Jerusalem will not only be for their good, but for the good of the world at large.”28

Towards the end of his stay in America, he met, in New York, with the President-elect of Mexico, and expressed his hope that Jews would continue to prosper in his country. He added that all countries which have favored Jews have enjoyed prosperity and Mexico, by welcoming the wandering Jews, would now also prosper.29

Rav Kook’s practice of publicly expressing Jewish pride was earlier displayed in England in 1917, after the Balfour Declaration was passed by the British Parliament. At a public gathering celebrating the event, rather than thanking the British government, Rav Kook congratulated it for having been privilege to assist the Jews in returning to Palestine.30 The dynamic relation between Israel and the other nations of the world which Rav Kook referred to in speaking to government officials, was elaborately formulated by him in his writings.31

The image of the Liberty Bell and the verse engraved upon it, evoked by Rav Kook in his message to the President, was again referred to by him in a speech on June 22 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where the bell is located. Rav Kook said that the bell was one which rang out the freedom of America. He explained that the verse engraved on the bell, “And you shall proclaim liberty throughout the land for all its inhabitants,” spoke of liberty achieved after forty-nine years of work. Freedom is so important, he said, that one must work forty-nine years to achieve it. This is true for the individual, to whom the verse is addressed, and much more so for a nation. He then placed a wreath of flowers on the bell and said that freedom can be a crown of thorns or a crown of flowers, depending upon how it is used. In America, freedom is used properly, and therefore, it is a crown of flowers.32

Rav Kook’s praise of American freedom may have been more than mere rhetoric. In his philosophical writings, freedom is a central concept.32a He writes that the creation of the world is grounded. in the notion of divine freedom of action, and Man’s task is to link himself to this freedom and thereby actualize his inner essence.33 Rav Kook may have felt that the freedom enjoyed in America would enable its citizens to realize this wider sense of the concept. As we will see, Rav Kook, shortly before his departure from America, discussed his view of the country’s Jewish community. When he first came to the country, he wrote to his son that it was a difficult exile for the Jews, despite its outer amenities.34 As he saw more of the country and its Jewry, however, his views began to change. In one city, he told his audience that America is the best exile for the Jews, because of its concept of liberty. He added, however, that it is still better to be in Eretz Yisrael, because, elsewhere, the Jew is ultimately a stranger, while in Eretz Yisrael he is in his own land.35

Rav Kook himself, as we have seen, was very reluctant to travel to America. Besides the fact that he had many pressing matters to attend to in Palestine, his strong attachment to the land made it very difficult to leave. In New York, he told a reporter that Eretz Yisrael was part of his very soul, and leaving it was akin to having part of his soul removed.36 This feeling was apparently so strong that it projected itself onto Rav Kook’s visage. One reporter, describing his impressions of Rav Kook when he first arrived in New York, wrote that he was a very outgoing person, very eager to meet people and involved in the world, yet, at the same time, looked like a stranger, really wanting to be somewhere else.37

Despite Rav Kook’s physical distance from Eretz Yisrael during his stay in America, the land was uppermost in his thoughts. He urged American Jews to buy land and build industry there, and, if possible, to emigrate.38 He also attended to Palestine affairs while in this country. A major issue of importance at that time was the effort of the chief rabbinate of Palestine to gain the right to decide on matters of constitution and administration of wakfs, or properties donated for religious purposes in Palestine. Rav Kook had been working on this matter before leaving for America, but the official decision was still pending. While in Washington, he discussed the matter with the British ambassador.39 In May, 1924, an ordinance was passed giving the chief rabbinate the control they sought. This ordinance strengthened the power of the chief rabbinate and was vigorously opposed by both leftist, anti-religious factions, and by the old community of Jerusalem, led by Rabbi Hayyim Sonnenfeld. Rabbi Sonnenfeld sent a cable to the British Colonial Office, asking that the right of decision concerning the wakfs should remain with the Moslem Religious Court, as it had until then, rather than with the “Zionist Chief Rabbinate.” The Colonial Office, however, rejected the appeal, saying that the ordinance could not be annulled.40

Rav Kook’s Yeshiva and Degel Yerushlayim

While in America, Rav Kook also spoke of the yeshiva he was in the process of creating in Jerusalem. In 1922, a small group of young Talmudic scholars began to study in his bet ha-midrash. From this core group, he hoped to develop a Torah institution which, together with the institution of the chief rabbinate, would turn Jerusalem into the spiritual center of world Jewry. The group was referred to as "Merkaz Ha-Rav", because Rav Kook felt it was not large enough to merit the title of ‘yeshiva'. He hoped to name it eventually the Central Universal Yeshiva, to which young scholars from all parts of the world would come to study.

The physical aspect of Eretz Yisrael, Rav Kook said, constituted ‘Zion,’ while its spiritual aspect constituted ‘Jerusalem.’ He insisted that Zion has significance only if it culminates in Jerusalem. He called his campaign to realize this goal of developing the spiritual nature of Jerusalem, Degel Yerushalayim, “Banner of Jerusalem”, a movement which he actually started during his years in London, from 1917 to 1919. In interviews and public addresses he gave during his stay in America, he spoke enthusiastically of this project.41 At an OU convention, he said that he envisioned joint cooperation between his projected yeshiva and RIETS, including exchange of faculty, the sending of RIETS students to his yeshiva for a certain period of time, and contributions of RIETS students and faculty to a future Torah journal.42 In a letter to his son, he wrote that his central purpose in coming to America was to gain support for the yeshiva.43 However, because of his obligations to the CRC, he did not make a formal effort to raise funds for his own yeshiva until a few days before he left the country, when the business of the Torah Fund had already been concluded. At that time, he set up an American committee to aid the yeshiva, headed by Rabbis Aaron Teitelbaum, Israel Rosenberg, Bernard Levinthal, and others.44

Although the rabbinical delegation was in America primarily to raise funds for Torah institutions overseas, they dealt with other issues, as well. Rabbi Shapiro, for example, made an appeal-through the politically active Rabbi Simon Glazer of New York-to Secretary of State Charles Evan Hughes, to permit prospective haluzot entrance to America, despite recently passed laws which severely limited foreign immigration.45

The delegation was often called upon to arbitrate conflicts between rabbis and rabbinical organizations. Rav Kook was again the spokesman for the group in these cases. Their efforts in this area met with mixed success. In Pittsburgh, a peace agreement adopted through the mediation of the delegation by two rabbis in the city, made front-page headlines in the local Yiddish press.46 In Montreal, on the other hand, the delegation was unable to find a solution to a conflict involving kashrut supervision, as one of the factions refused to submit to their authority.47 In Newark, Rav Kook proposed a rapprochement between two rabbis who had been disputing the rights to supervision of certain slaughterhouses in the city. When one of the rabbis refused to make peace, Rav Kook in turn refused to attend his installation as spiritual leader of a local synagogue. Rabbi Shapiro also declined the invitation, while Rabbi Epstein, having been the teacher of that rabbi in Slabodka, did attend. He went, however, only as a private individual, not in his official capacity as a member of the rabbinical delegation.48

The importance of rabbinic unity was constantly stressed by the delegation while they were in America.49 Rav Kook felt that Jerusalem should serve as a unifying factor in this area. By establishing a universal rabbinic organization there, such unity could, he felt, be achieved.50

Conflict with Keren Hayesod

A difficulty encountered by the CRC in its Torah Fund was its convergence with the campaign of the Keren Hayesod, the financial arm of the World Zionist Organization. In connection with this campaign, Hayyim Weizmann had come to America around the same time as the rabbinical delegation. The coincidence provoked wide-scale criticism. The Hebrew weekly Hadoar, for example, wrote that despite the importance of the Torah institutions of Europe and Palestine, they felt the campaigns for the Tarbut schools overseas and for the Keren Hayesod, both already underway, should take precedence, and that the CRC should delay the beginning of its Torah Fund campaign until the others are completed.51 Other voices suggested that the conflict in scheduling was a deliberate attempt by the CRC and the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim which helped coordinate the campaign, to undermine the Keren Hayesod because of it irreligious character.52 Whether or not this allegation was true, the conflict worked to the detriment of the Torah Fund, which fell short of its one million dollar goal.53

The irreligious nature of the Keren Hayesod was, indeed, an issue being raised in Orthodox circles in America at the time. In 1923, Rabbi Simon Glazer, an ardent Zionist worker, who had almost single-handedly brought about the joint congressional resolution recognizing the Balfour Declaration,5454 sharply criticized the Keren Hayesod at the 1923 convention of the Knesset Ha-Rabbanim, a rabbinic organization run by Rabbi G.Z. Margolis together with Rabbi Glazer. The result of this criticism was the organization’s withdrawal of support for the Keren Hayesod, and its official alignment with the Agudat Israel World Organization.55 In 1924, the Morgen Journal ran a series of articles critical of the Keren Hayesod, and at the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim convention in May of that year, one participant suggested a move similar to that of the Knesset Ha-Rabbanim. Rav Kook, who was present at the convention, spoke against the proposal, and vigorously defended the work of pioneers in Eretz Yisrael, who were selflessly dedicated to rebuilding the land. He also warned the rabbis not to engage in overhasty zealousness.56 It is possible that some of the rabbis present knowing of Rav Kook’s recent protest against public Sabbath violation in Palestine57, and his support of a law in Tel Aviv making such violation a civil crime58, felt that the rabbi would approve of withdrawal of support for the Keren Hayesod. In actuality, they totally misread Rav Kook’s position. One reporter, present at the convention, wrote that he had spoken to many of the rabbis present there about Rav Kook, and discovered that they really knew very little about his views.59

Rav Kook’s support of the Tel Aviv Sabbath legislation provoked quite a different reaction from the previously cited reporter for the Forward. He wrote with anger that Rav Kook wanted to impose religious rule in Palestine, and that such an approach was in opposition to the ideals of democracy, socialism and free thought.60 This criticism was echoed in other Jewish socialist papers and reflected that movement’s attitude towards religion. As spelled out in one of the papers of the time, they were willing to tolerate religious Jews as long as they did not attempt to impose their religion on others.61 The reporter for the Forward, in fact, also interviewed Rabbi Shapiro, and was much more satisfied with his remarks than with Rav Kook’s. Rabbi Shapiro told him that, although he was not happy with the Jewish cultural schools being built in Lithuania, he would never complain to the government about them, since it was an internal Jewish issue. The reporter felt that it was this approach, rather than Rav Kook’s, which had enabled the Jewish people to survive throughout its long period of exile.62

Because of the conflict with the Keren Hayesod campaign, the CRC cancelled its original plan to have the rabbis visit Chicago near Pesah time and make appeals in synagogues during that holiday. The CRC had hoped that a generous response in Chicago would serve as an example for the other cities which the rabbis were to visit. However, the Keren Hayesod, which had already designated the last day of Pesah as a day to make appeals for their campaign in Chicago, protested the projected appearance of the rabbis, and prevailed upon the CRC to arrange a different date for their Chicago campaign. They decided that the rabbis would visit other cities first, and come to Chicago for Shavuot.63

Montreal

The first major city visited by the rabbis as a group was Montreal. On their arrival in the city on May 5, they were greeted by more than two thousand Jews at the train station. From there, they were driven in an automobile procession to City Hall, where they were greeted by Mayor Duquette. The mayor spoke highly of the Montreal Jewish community, and wished the rabbis success on their mission. Rav Kook, in his reply, referred to Montreal as one of the greatest British cities outside of England. He said that Canada was a sister country of his, since Palestine was under British protectorate rule, and that he was, therefore, a British subject. He praised the British government for helping the Jews build a home of their own. He added that,

When all is said and done, the difference of religious belief is only on the surface, the fundamentals being, to do good to all mankind, live up to the teachings of the Bible and carry out the precepts of the Golden Rule.

At a fund-raising banquet the next evening, Rav Kook said that the Torah is the source of the Jew’s past and future. A reporter present wrote that the speech revealed a wealth of scholarship and erudition, and that hearing it was like watching the flow of a placid stream, whose source is inexhaustible. Six thousand dollars were pledged that evening to the Torah Fund.64

Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit

The next city visited by the rabbis was Pittsburgh. They were in the city on May 18 and 19. While there, they visited the Hebrew Institute, where Rav Kook addressed the children in Hebrew. As mentioned earlier, the delegation was able to make peace among the local rabbis. One Pittsburgh resident, Mr. Charles Levin, was so pleased with this development that, in appreciation, he gave one hundred dollars to Rav Kook, to use for the Institute for the Blind in Jerusalem.65

The next stop for the rabbis was Cleveland, which they visited from May 20 to 22. Although there was a large reception for them at the train station when they arrived in the city, there was a very poor turnout at the banquet held the next evening, at which only $1,500 was raised for the Torah Fund. Before leaving, the rabbis criticized the community for its poor response, and suggested that a fund be set up in the city to help support the CRC.66 Interestingly, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, in describing Rav Kook, noted that he had a reddish beard, wore a squirrel cap, and spoke the Hebrew which Jews in Palestine had spoken two thousand years before.

The rabbis next visited Detroit, from May 27 until June 2. At a banquet on May 29, Rav Kook spoke of the essence of Jewish nationality, and the essential unity in moral purpose of the various elements among the Jewish People. In discussing the significance of the galut [exile], he said, “The past, present and future form a constant stream of the history of our people, and constitute one process.”

The redemption of our people, both in a physical and spiritual sense is determined by the manner in which the Jewish will asserts itself... American Jewry constitutes that phase of present Jewish life which makes possible the necessary adjustment in life of our people as a whole. The present sufferings of the Jewish People in Eastern Europe, on the one hand, and the Zionist activities, on the other, are the signs of the coming Jewish rebirth. 67

One Detroit reporter, in describing his impressions of Rav Kook, wrote of the importance of his rabbinic position and his impeccable scholarly credentials. However, he wrote, the rabbi was most of all a poet-philosopher, whose large, kind eyes contained a suggestion of the mystic, and that his sympathy for his people and for the world, dominates his outlook upon the problems of the Jewish People, the strangeness of its historical evolution, its sufferings and its efforts to achieve a more or less cohesive adjustment. Like an ancient prophet, wrote the reporter, Rav Kook sees a final resolution of his people’s and humanity’s problems on the basis of reason, justice and enlightenment. The reporter, Abraham Caplan, concluded that, “As close as Rav Kook is to his people, whom he loves with such a love few others have, he moves in a lofty mental sphere and detaches himself from the maddening crowd.”68

Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore

After leaving Detroit, the delegation went to Chicago, arriving there on June 2, and remaining there for a week, through Shavuot. Chicago was their major stop outside of New York City, and they raised over fifty thousand dollars there, of which the local press was very proud.69 While in the city, Rabbis Kook and Epstein delivered shi'urim to the students and faculty of the Hebrew Theological College.

From June 2 to 24, the rabbis visited Philadelphia. Speaking at Independence Hall on June 22, Rav Kook expressed his hope that the freedom and equality of humanity, which the Liberty Bell proclaimed, might continue to be the inspiring message of America.70 At a mass rally held at the Academy of Music on June 24, Rav Kook said that the Jewish religion is the hope of the world, and Jerusalem the hope of the Jewish People. “We do not forget our bond with Zion,” he said, “and we do not permit the world to forget it.” 71

From Philadelphia, the delegation proceeded, on June 25, to St. Louis, and from there to Boston, where they arrived on July 1. A local Boston reporter, writing on Rav Kook’s speech at a banquet held in the city, noted that when he spoke of Zion and Jerusalem, one felt that he really meant what he said, and even those who couldn’t understand the speech itself sensed the holiness of his words.72

The rabbis next visited Baltimore, from July 6 to 8. The local Jewish press wrote enthusiastically of their cause, and urged the city’s Jews to contribute.73 Rabbi Israel Miller of Yeshiva University, recalled Rav Kook’s visit to the local talmud torah which he was then attending. After he addressed the student body in Yiddish, the students filed past him individually to receive his blessing. Rabbi Miller particularly remembered the kindness projected through Rav Kook’s eyes,74 a feature also mentioned as we have seen by Abraham Caplan of Detroit.

On July 8, the rabbis returned to Chicago, where they remained for a few more days, and then finally returned to New York, in anticipation of their departure from America. They did not personally travel to cities further west, but representatives of the CRC went to cities such as Denver, Kansas City, Los Angeles and San Francisco to raise money for the Torah Fund.75 In addition, the Agudat HaRabbanim had its members pledge to spend two weeks each, traveling to smaller cities which did not have rabbis, in order to raise funds.76

Throughout their stay in New York, special receptions were held for the rabbinical delegation in various communities of the city, including Brownsville, East New York, Harlem, Boro Park, and others. They also occasionally visited private individuals. For example, the delegation visited the home of Rabbi Israel Rosenberg, a leader of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim and the CRC, where a special meal was prepared in their honor.77 This was one of the few places where Rav Kook ate anything other than what was prepared for him by his private cook, or by his son-in-law, Rabbi Israel Rabinowitz Teomim, who had accompanied him on his trip to America.78

Another home in which Rav Kook consented to eat, was that of Dr. Samuel Friedman, popularly known as “Shabbos” Friedman, because of his rare status as a Sabbath-observing physician. Dr. Friedman’s son, in his biography of his father, described an interesting incident that occurred while Rav Kook was visiting his parents’ home in Edgemere, New York. A distraught man interrupted a conversation between Rabbi Kook and Dr. Friedman, and told the doctor that his ailing daughter had no chance to live, and that, therefore, Dr. Friedman was her only hope for survival. Rav Kook told the man to pray, but the man said he couldn’t, because he was a Sabbath-violator. Rav Kook told him that if he wanted his child to live, he must repent and decide to observe the Sabbath. He then told Dr. Friedman to tend to the child, who, in the end, survived.79

Farewell Banquet

The rabbis had originally planned to stay in America for about three months.80 However, because their fund-raising efforts were not as successful as had been hoped, they remained for eight months. In the end, they raised a little over $300,000, far short of the one million dollar goal which the CRC had set. Before leaving, the rabbis helped set up a membership drive for the CRC, which it was hoped, would bring in more funds.81 In any case, in May, 1925, the executive committee of the JDC decided to reorganize its work for all spheres of relief, and thus, the CRC rejoined the organization, thereby considerably relieving themselves of fund-raising burdens. The money raised by the rabbis, therefore, proved to be quite helpful for the short period of time during which it was needed.82

The rabbinical delegation left America on November 12, 1924. During their last few days in the country, farewell receptions were given them by various organizations. At a banquet held on Sunday evening, November 9, by the CRC, the rabbis thanked American Jewry for its help in saving the Torah centers in Europe and Palestine. Rav Kook, in his speech, said that the CRC campaign should not be taken in isolation from other campaigns, because all Jewish spiritual efforts are interconnected, and lead to Israel’s ultimate redemption.83

On Tuesday afternoon, November 11, a special farewell ceremony for Rav Kook was held by the Zionist Organization and the Keren Hayesod. The event was attended by about five hundred of the leading Zionist and Keren Hayesod workers of Greater New York. The famed orator, Reverend Zevi Hirsch Masliansky, opened the ceremonies by praising Rav Kook for his spirit of tolerance towards people with whose religious views and practices he differed most radically. Another speaker Gedaliah Bublick, editor of the Yiddish daily, the Tageblatt, declared that Rav Kook represented the inseparable union of the Jewish religion and Jewish nationalism.

In his farewell address, Rav Kook spoke of recent events in Jewish history, of the first steps in the great redemption, and predicted that “in the final structure, the material and the spiritual will be harmoniously blended in truth to the fundamental character of the Jewish People.” He also spoke of the halutzim, the Jewish pioneers in Palestine, and predicted that the workers for the spiritual redemption of Palestine and they will ultimately say “Amen” to each other, united in common purpose.84

On November 12, at 9:00 A.M., the rabbinical delegation was met at Pier 59 by thousands of Jews, wishing them a safe journey. The rabbis issued a letter of farewell to American Jewry, wishing them the blessings of the Torah, and asking them to become members of the CRC and thereby continue to support Torah institutions over-seas. Their ship, the Mauretania, departed at 11:00 that morning.85

Reporters were very interested in the impression the rabbis had of America, and especially in those of Rav Kook. In an exclusive interview he had with the Morgen Journal, Rav Kook referred to American Jewry as a hidden treasure, and enumerated three qualities they had which, if developed, could make them one of the most important Jewries in history. These qualities were a deep feeling for religiosity, a sense of Jewish nationalism, and a sense of social responsibility. He attributed the last quality to the excellent human material of which the Jewish communities consist, as well as to the civil liberties enjoyed by American Jews as free citizens of a republic under a generous and democratic government. He also noted the importance of the civic education which American Jews receive through their unhampered participation in their country’s political affairs.

In order for American Jews to develop their potential, Rav Kook said, it is necessary for them to provide a proper Jewish education for their youth. To this end, he felt that parochial schools should be built by the Jewish community. He felt that American Jewry would eventually surpass Jewries in other lands of the diaspora and serve as an example for them, and ultimately, would be able to transfer its talents to Palestine to help rebuild the Jewish homeland.86 These last remarks echoed those he made at an OU convention in June, where he said that, just as in the past, there were two great centers of Jewry, Palestine and Babylonia, so today, there are two great centers of Jewry, Palestine and America.87

Rav Kook maintained contact with the American Jewish community after returning to Eretz Yisrael, largely in connection with the committee he had set up in New York to aid his yeshiva. He planned a return trip to this country to raise funds for the yeshiva, but was never able to make it.88 He was occasionally asked for his opinion of events on the American Jewish scene,89 and one of his last acts before he died, was to send a telegram to the Agudat HaRabbanim of America expressing his opposition to proposed changes in the ketubah sponsored by the Conservative movement.90

Rav Kook’s trip to America came at a watershed period in Jewish history. Immigration laws passed in 1921 and 1924 had in effect put an end to the mass influx of Eastern European Jews to America, a process which had begun in the 1880’s. A time for consolidation had come, and Rav Kook’s visit with his two colleagues gave American Jewry an opportunity to take stock of itself, and consider its strengths and weaknesses. The appearance of the rabbinic delegation in America helped bolster the community’s self-image, and the honor shown the rabbis by public officials greatly strengthened Jewish pride. The message received from the rabbis, and especially Rav Kook, was that America, which had been considered earlier a "treife medinah", was now beginning to emerge as a major center of Jewish religious life. It was widely felt that the rabbis’ visit did more for American Jewry than for anyone else.91 Rav Kook’s unique contribution was his promotion of love for Eretz Yisrael and support for its physical upbuilding, especially at a time when voices of opposition were beginning to be heard in the religious community.

A Reporter’s Impressions

What follows are the impressions a writer for the English section of the Tageblatt, Jean Jaffe, had of Rav Kook upon meeting him at the Hotel Pennsylvania.

It is impossible to speak of Chief Rabbi A. I. Kook without becoming sentimental, at times even maudlin. I witnessed the hardy reception tendered to the rabbi by Mayor Hylan of New York. I was moved by the occasion for, literally speaking, his patriarchal countenance and prophetic mien brought tears not only to the eyes of his fellow rabbis present, but to the eyes of many a transient street gamin as well as the municipal officials.

I read of Rav Kook’s versatility. I heard of his rare spirit. I knew of his literary work. I heard of the numerous titles conferred upon him. I was familiar with the rabbi’s achievements in the spiritual and physical development of Palestine. When I went to meet him I therefore awaited a spiritual bulwark, a gigantic mind. And I found much more.

I was admitted into an attractive reception room at the Hotel Pennsylvania where a host of people, from indifferent newspapermen to rabid enthusiasts and disciples of the rabbi, were eagerly awaiting him. I admit that my short knowledge of Hebrew, to which I immediately resorted, made me feel more at ease (I was the only woman present) and made my presence more desirable.

Rabbi Kook was ushered in from the adjacent room. I sincerely hoped that it were possible for me to remain silent throughout. I wanted to sit, look and listen.

I managed to be the last one confronted, so that I might have time to stay. I looked at the calm, celestial face illuminated by the large, Semitic eyes, which spoke of sorrow and impression, of poetry and hope-and of wisdom. I noticed his white, well-kept hands as he removed his massive headgear to the surface of a skullcap. I looked at his beautiful, immaculate garb, black velvet and white. I followed up closely his consistent resort to the Talmud which he brought in under his arm and from which he would raise his eyes only to answer questions, which were provoked by his own replies.

It is quite a revelation to hear a well-constructed, well-modulated English come from so aged a man (Rabbi Kook is about sixty) who has spent his life in Russia and Palestine. He later accounted for it by saying that frequent meetings with Herbert Samuel led him to make a study of the language. He did it by a thorough study of an English translation of the Bible.92 Rabbi Kook speaks German, Russian, French and Chaldean, besides Hebrew and English.

His tone was quite jovial for he mostly answered questions about the things nearest to him, the Torah and Palestine. But when putting questions, his tone was grave, for he asked of the galut, of the desecration of the Bible, of the violation of the Sabbath. He would often abandon the topic under discussion and with the intellect of a father would ask personal questions of each respective guest. He was able to discuss freely modern phenomena and types and phases of modern life.

Rabbi Kook was most impressive when he struck the lyric chords. He turned poet in expression and ardor when he spoke of the great number of Jewish colonies springing up in Palestine, of the development of industry and natural resources. Then his face beamed all the more as he told of a railroad between Tel-Aviv and Lod, which is not operated on the Sabbath.

The words ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘inspiration’ constantly echo in his conversation. “Jewish children must be inspired to the Bible and by the Bible,” was one of his frequent remarks. Another was, “The building up of Palestine must be with dignity and religion.”

I came away from this venerable man with a vision of all that I ever knew and heard of the Jewish race, with an intense feeling for the things he conveyed and with a feeling of annoyance against all the pettiness of everyday life which surrounded me upon my departure. 93

Notes

a.Rav Kook’s Mission to America by Joshua Hoffman. Originally printed in Orot, A multidisciplinary journal of Judaism, vol. 1, 5751 (1991), pp. 78-99. Subtitles, formatting, and photos were added to make this fascinating article more web-friendly.

1. The Sefer Ha-Yovel shel Agudat Ha-Rabbanim: 1902-1927 (New York; Agudat Ha-Rabbanim, 1928), p. 125, states that the AJRC was started by “reformed Jews” who called for a general meeting, led by bankers and leaders of the American Jewish Committee. This group asked the CRC to join with them to form one united relief committee; The CRC, however, insisted on retaining its separate existence, in order to assure that the needs of the Orthodox world would be attended to. Oscar Hardlin, in The Continuing Task (New York, 1964), p. 25, writes that the American Jewish Committee had asked forty national organizations to meet in October, 1914. At that meeting, Oscar S. Strauss, Julian V. Mack, Louis D. Brandeis, Harry Fischel and Meyer London were charged to select one hundred people to act as the AIRC, with Louis Marshall serving as president and Felix M. Warburg as treasurer. Harry Fischel also served as treasurer of the CRC, while Louis Kamicky, publisher of the Yiddish daily, the Tageblatt (Jewish Daily News), served as its president. See also Aaron Rothkoff’s article, "The 1924 Visit of the Rabbinical Delegation to the United States of America,” in Ha-Masmid (New York, 1959), p. 122. Rothkoff incorrectly identifies Kamicky as publisher of the daily, Morgen Journal.

2. Yeshiva University Archives, records of the Central Relief Committee, 198/8.

3. Ibid. 140/1.

4. Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 177, no. 1212, and CRC, 140/2.

5. The Hafetz Hayyim was in his eighties, and too ill to travel, while Rav Hayyim Ozer had recently lost his wife. Rav Kook wrote R. Hayyim Ozer a letter of condolence shortly before leaving for America. See Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 185, no. 1222. Until then, he had tried to convince R. Hayyim Ozer to join him in the trip. See, for example, Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 175, no. 1207. The Morgen Journal, April 16, 1924, published a letter from R. Hayyim Ozer, expressing his regret that he couldn’t come, and referring to the members of the delegation as being the greatest geonim of the generation.

6. Morgen Journal, Jan. 31, 1924, p. 1. That paper reported that 150 rabbis attended a reception for Rabbi Epstein.

7. Rothkoff, op. cit., p. 123.

8. Ibid.

9. Morgen Journal, March 21, 1924, p.9.

10. Ibid, March 20, 1924, pp. 1 and 2, and Tageblatt, March 20, p. 1. The Tageblatt article included a Yiddish translation of Rav Kook’s Hebrew speech.

11. Rothkoff, op. cit., p.124.

12. See, for example, Der Tag, April 3, 1924.

13. Y. U. Archives, CRC, 140/6.

14. See, for example, the report in the Tageblatt, March 20, 1924, p. 1.

15. Boston Jewish Advocate, March 1, 1912, p. 6.

16. Tageblatt, March 20, 1924, p. 1. See also The Jewish Forum, March, 1924, pp. 173-176 (and also June, 1924, p. 367, for corrections of errata in the March article).

17. Forward, March 26, 1924, p. 7.

18. Iggrerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 189, no. 1229. Rav Kook was referring to the passage in Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 5a which states that afflictions can be identified as “chastisements of love”, if they do not cause loss of time from prayer or Torah study. See also the quotation in Rothkoff, op. cit., p.125. Rabbi Israel Tabak, who came to America on the Olympic at the same time as Rabbis Kook and Shapiro, related his impressions of these rabbis in his memoirs. Of Rav Kook he wrote,

Rav Kook impressed me as particularly serious, steadfast of purpose, and always deep in thought; he invariably held a sefer close to him, and was constantly engaged in study or contemplation. His face reflected his strong character, his determination to get things done, to make every day count. In spite of his fame and his important position as Chief Rabbi, he was modest and reserved and never assumed an air of superiority. (Three Worlds, A Jewish Odyssey, by Rabbi Israel Tabak, Jerusalem, 1988, p.93).

Rabbi Tabak erroneously states (ibid.) that Rabbi Epstein was on the Olympic together with the other two rabbis.

19. Ibid, pp. 195-196, no. 1241.

20. Das Yiddishe Licht, April 18, 1924, p. 19.

21. Tageblatt, April 3, 1924, p: i

22. Ibid, April 6, 1924, p. 7.

23. Das Yiddishe Licht, May 2 1924, pp. 4-5.

24. Tageblatt, April 3, 1924 p. 1

25. Morgen Journal, April 16, 1924 p. 1.

26. CRC, 140/7. The CRC records contain an English translation of Rav Kook’s entire speech, and fragments of President Coolidge’s speech.

27. Morgen Journal, April 16, 1924, p. 2.

28. Canadian Jewish Chronicle, May 9, 1924, p. 5.

29. Jewish Daily Bulletin, Oct. 30, 1924.

30. Alexander Carlebach, Men and Ideas (Jerusalem, 1982), p. 109.

31. See, for example, Orot, pp. 15-17.

32. The Philadelphia Jewish World (Yiddish), June 23, 1924.

32A. See e.g. Eder Ha-Yeqar, p. 28; Iggerot Rayah, vol.1, p. 53; no. 44; Orot ha-Qodesh, vol. 3, p. 40; vol. 4, p. 423; Arpiley Tohar, bot. p. 57; Eretz Tzvi [Tzvi Glatt Memorial Volume] (Jerusalem, 1989) p. 183, par. 2; Rabbi M.Z. Neriyah, Sihot ha-Rayah (Tel-Aviv, 5739) note bottom p. 342.

33. Orot Ha-Qodesh, vol.3, p.26.

34. Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4. p. 190, no. 1231: "Galut kevedah hi, ela she-me'uteret bi-zehuvim” (“It is a heavy exile, but adorned with gold coins”).

35. Philadelphia Jewish World, June 23, 1924, and Baltimore Jewish Times, May 23, 1924. See also, Orot, p. 11 (6).

36. St. Louis Jewish Record (Yiddish), June 13, 1924.

37. Morgen Journal, March 23, 1924, p. 4.

38. Ibid, March 20, 1924, p. 2.

39. Ibid, April 16, 1924, and CRC, 140/6.

40. Chicago Chronicle, June 13, 1924, and Morgen Journal, June 10, 1924, p. 9, which carries a report from Jerusalem, dated May 10. See also Iggerot LaRayah (Jerusalem, 5750) p.257.

41. Morgen Journal, April 29, 1924, p. 6; Das Yiddishe Licht, July 25 and August 8, 1924.

42. Das Yiddishe Licht, May 30, 1924, English section, p. 12, and sources in note 40. See also Iggerot La-Rayah (second, enlarged edition, Jerusalem, 5750) pp. 325-326, no. 215.

43. Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 190, no. 1231.

44. YU Archives, CRC, 124/1 and 5.

45. The Glazer Papers, American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio. The prospective halutzot were widows whose husbands had died childless, and were survived by a brother. The woman could not remarry unless halitzah was performed with the surviving brother. Often, the brother was in America and the widow overseas.

46. The Jewish Indicator (Yiddish), May 11, 1924, and Der Tag, May 23.

47. The Canadian Eagle (Yiddish), May 11, 1924, and Der Tag, May 23. On the entire controversy, see Ira Robinson, “The Kosher Meat War and the Jewish Community Council of Montreal, 1922-1925,” in Canadian Ethnic Studies, vol. XXII, No.2, November 30, 1990.

48. Ya’akov Mendelssohn, Mishnat Yavetz (Newark, 1925), p. 72. Rav Kook is referred to as "rosh ha-medabrim,” the spokesman of the group.

49. See, for example, Morgen Journal, May 14, 1924 and Nov. 10, 1924, p. 1. Rav Shapiro attributed the failure to reach the CRC’s one million dollar goal to the lack of unity among American Jewry.

50. See sources in note 40.

51. Hadoar, March 21, 1924, p. 2, and March 28, p. 1. In its Nov.14 issue, the journal further criticized the delegation for not having rebuked American Jewry on account of its low level of religious observance.

52. Newspaper article by B.Z. Goldberg, dated March 24, 1924. The article is included in a collection of press clippings in CRC, 206. The newspaper is not identified, but appears to be Der Tag.

53. In a letter to the Chief Rabbi of South Africa (CRC, 124/5), Rav Kook wrote that, despite all the honor shown him in America, he was unable to raise enough money to establish a firm foundation for the yeshivot.

54. See his work, The Palestine Resolution (Kansas City, Mo., 1922). He sent a copy of it to Rav Kook. See Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, pp. 155-156, no. 1169.

55. Das Yiddishe Licht, July 27, 1923, p. 8.

56. Der Tag, May 20, 1924 (in CRC, 205).

57. Das Yiddishe Licht, April 4, 1924, English section. p.10.

58. Forward, March 26, 1924, p. 7, and Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 160, no. 1179.

59. Der Tag, May 20, 1924. Also, see Ha-Doar, May 30 and June 6. The article in the May 30 issue gave the impression that many members of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim backed the proposal in question. In a letter to the editor in the June 6 edition, R. Hayyim Hirschenson explained that it was the proposal of only one person, who himself was an outsider, and not a member of the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim. The article in Der Tag seems to corroborate the May 30 Ha-Doar version. Later, in the winter of 5686 (1925-1926), Rav Kook was criticized by a group of Hasidic rabbinic leaders for his support of the Keren Ha-Yesod. See article by R. Ya’akov Filber in Ha-Zofeh, 3 Ellul, 5750, p. 8 and Iggerot La-Rayah (Jerusalem, 5750) pp. 303-306, no. 199.

60. Forward, March 26, 1924, p. 7.

61. Der Wecker, April 12, 1924 (in CRC, 206).

62. Op. cit.

63. CRC, 140/9 and 11.

64. Canadian Jewish Chronicle, May 9, 1924, pp. 5 and 9.

65. The Jewish Indicator, May 27, 1924.

66. The Cleveland Jewish World (Yiddish), May 23, 1924.

67. Detroit Jewish Chronicle, June 6, 1924.

68. Ibid.

69. Chicago Jewish Courier, June 11, 1924. In an article on June 4, the Courier suggested that the rabbinic delegation meet with the directors of Chicago’s Hebrew Theological College (now located in Skokie) to determine the direction the institute should take, and what balance should exist in the curriculum between Talmud and other Jewish studies.

70. The Philadelphia Jewish World (Yiddish), June 23, 1924.

71. Ibid. June 25, 1924.

72. Clipping from a Boston Yiddish newspaper, in CRC, 206, dated July 3, 1924. Rav Kook was accompanied on his trip to Boston by Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Charlop, who had come to New York to deliver the money collected during a Shavuot appeal for the Torah Fund in four synagogues in Omaha, Nebraska, which he served as rabbi. See the Omaha Jewish Press, July 10, 1924, and Mikhtevei Marom (Jerusalem, 5748) p. 63. That work contains letters sent to Rabbi Charlop by his father, R. Ya’akov Moshe, who was a very devoted student of Rav Kook. In a conversation (Nov. 14, 1990), Rabbi Zevulun Charlop of RIETS, a son of R. Yehiel Mikhel, related that in an unpublished letter, his grandfather prompted R. Yehiel Mikhel to make the trip from Omaha to New York. In other unpublished letters, R. Ya’akov Moshe wrote to his son of his attempts to dissuade Rav Kook from traveling to America, and of Rav Kook’s attempts to persuade Rav Charlop to accompany him on the trip.

73. Baltimore Jewish Times, July 4, 1924, p. 10.

74. Conversation, September, 1990.

75. Denver Jewish Times, August 14, 1924.

76. Sefer Ha-Yovel shel Agudat Ha-Rabbanim, p. 62.

77. Conversation with J. Mitchell Rosenberg (Rabbi Rosenberg’s son) on December 17, 1989. Mr. Rosenberg recalled that Rav Kook told him of a meeting he once had with President Wilson (sic). Rav Kook said that he had explained to the President the Jewish concept of the Messiah, and that the President had understood what he was told.

78. Leonard Seymour Friedman, in The Angel Cometh (New York, 1986), p. 136, mentions this precaution taken by Rav Kook. The other members of the rabbinic delegation also seem to have acted in this manner. See CRC, 140/11, telegram from Rabbi Teitelbaum to B. Horwich, dated April 17, 1924.

79. Ibid. pp. 113-115.

80. Morgen Journal, March 21, 1924, p. 9.

81. CRC, 124.

82. CRC, 198/8.

83. Morgen Journal, Nov.10, 1924, p. 1

84. The New Palestine, Nov.14, 1924, p. 323. See also Ma’amrey Ha-Rayah (Jerusalem, 5744), pp. 94-99.

85. Morgen Journal, Nov. 13, 1924.

86. Ibid, Nov. 12, 1924, p. 2, and Jewish Daily Bulletin, Nov. 13, 1924, p. 2. See also The Jewish Forum, September, 1924, p. 558, and Iggerot Rayah, vol. 4, p. 201, no. 1149.

87. Das Yiddishe Licht, May 30, 1924, English section, p. 12.

88. CRC, 124/6.

89. Ibid.

90. See London Jewish Chronicle, Sept. 6, 1935, p. 12, and Hayyim Karlinsky, Divrei Yosef (New York, 1947), introduction, p. 39. The proposal provided for an authorization by the husband, at the time of marriage, to allow his wife to appoint an agent to write a get and another agent to deliver it. This authorization was to be spelled out in the text of the ketubah. The proposal was made by Rabbi L. Epstein, who claimed that Rav Kook approved i In his telegram, Rav Kook expressed his opposition to the proposal. In a letter to R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski, also cited by Karlinsky, Rav Kook wrote that he had never heard of Epstein. An account of the proposal and the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim’s campaign against it, is given in Karlinsky’s work, introduction, pp. 31-44, and in the work Le-Dor Aharon, published by the Agudat Ha-Rabbanim in New York, 1937.

91. Editorials in newspapers at the time of the delegations’ departure.

92. Rav Kook received English instruction while a resident of London. In a letter to the London Jewish Chronicle, Sept. 13, 1935, p. 12, Rabbi Dr. S. M. Lehrman writes:

It was my never-to-be-forgotten privilege to be his disciple in Talmud and Poskim and also to become his first English tutor. A more brilliant pupil could not be imagined. Together we read also the classics of other European languages, of which he possessed such an excellent knowledge.

93. Tageblatt, March 28, 1924, English section.