The following description of Purim festivities in Rav Kook’s home in Jerusalem, celebrated together with students from his yeshiva, took place in the 1930s, under the shadow of the rise of Nazi Germany.

Rav Kook, who had studied in the famed Volozhin yeshiva in his youth, transplanted the Volozhiner Purim merriment to his own yeshiva in Jerusalem, Mercaz HaRav.

Just as he would completely immerse himself in the special holiness of the Sabbath and holidays, so too, the joy of Purim would radiate from his entire being. On Purim, his happiness was evident in his exuberant speech; in his eyes, lit up like two merry torches; in the quickness of his movements; and in the lively content of his Purim Torah.

The joy began on Purim evening. The yeshiva students hastened to the Rav’s house wearing a riot of masks and costumes. Some were clothed in the long black coats worn by rabbis and rabbinical judges; others dressed in the shtreimels and colorful striped cloaks typical of the ultra-Orthodox of Jerusalem. A few arrived with exotic turbans and keffiyehs, while others wore the flat caps and short-sleeve shirts of manual laborers.

The Purim festivity was a mixed multitude of colors and hues, a cacophony of singing, cantorial renditions, Talmudic sing-song, and the melodious trope of Megillah reading. In addition to the yeshiva students, many prominent Jerusalemites showed up: Torah scholars and academics, political activists and writers, all of whom came to visit the Chief Rabbi in a time of exuberant happiness.

Rav Kook spoke of the simchah of the Jewish people, an inner joy that sings within the soul. This joy is not like the superficial delight of other nations, one that comes from transient pleasures and fades away in the blink of an eye. “O Israel, do not rejoice in joy like the nations” (Hosea 9:1). No, no, he emphasized. Our joy is fundamentally different.

Our custom is to wear costumes on Purim, the rabbi explained, because it is an auspicious time to frustrate the plans of the prosecuting angel. Temporarily, we adopt the customs of Amalek: we wear his clothes, become inebriated, and act frivolously. The prosecuting angel sees us as one of his own and forgets about us. In this way, the Sages’ directive to drink on Purim enables us to abrogate the evil designs of Amalek.

In the middle of his speech, Rav Kook suddenly stood up and began to sing with great elation, “Do not fear, My servant Jacob! Do not fear, do not fear!” (Jeremiah 46:27) Then, to confuse the prosecuting angel, he sang the same tune, but translated the verse to Russian. In the following talks, he interjected Russian, German, and English words, thus adding to the general Purim spirit.

When the festivities reached their height, the Rav stood at the head of the table and began a lengthy Purim discourse. He examined every mitzvah in the Torah, interpreting each one as a source for the obligation to drink on Purim. With a wonderful blend of erudition and ingenuity, he derived from every mitzvah a metaphorical, homiletic, mystical, or even literal proof that one is obligated to drink “until one is unable to distinguish between cursed Haman and blessed Mordechai” (Megillah 7b).

Waging War on Amalek

That was the year in which persecution and violence burst forth across Germany. Synagogues were ransacked and set on fire; Jewish books were burned on public pyres; and Jews were beaten, robbed, and deported. Rav Kook sensed the impending Holocaust.

Suddenly, he rose, slid his hat to the side of his head like a soldier, girded his belt, and barked out like a drill sergeant, “Come, my sons! Let us forge a battalion to wage war on Amalek!”

Everyone stood at attention, and the rabbi marched before them. Shouting commands in garbled Russian, he led his ‘battalion’ through the corridors of the house. He sang, and they repeated after him, “Blot out! Blot out! Blot out the memory of Amalek!” He passed among the columns of ’soldiers,’ singing with a military tune, “Let the tribes of His nation sing His praise; for God will avenge His servants’ blood, and bring vengeance upon His foes” (Deut. 32:43). The rabbi’s eyes blazed, his body shook with emotion, and all marched after him in song.

Rav Kook then discharged the ‘troops’ and they returned to the yeshiva, where he lectured on the special portion of the Jewish people.

Our lot may be one of troubles, but nonetheless, “Fortunate is the people for whom it is thus” (Psalms 144:15). Even if we are persecuted all over the world, we are still privileged, since “Fortunate is the people for whom the Eternal is their God” (ibid).

Israel never truly sins. Even in the time of Haman, they only bowed to the idols to show their allegiance; they did not really worship them. Sometimes a Jew puts on a costume and pretends to be a sinner. But on the inside, he is as pure as crystal.

Amalek declared war on Israel. And precisely in times of war, we must engage in Torah study. In the terrifying abyss of the battle between purity and impurity, we make our home in the depths of Torah.

(Stories from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Mo'adei HaRe’iyah pp. 263-264; Celebration of the Soul, translated by R. Pesach Jaffe, pp. 125-126)

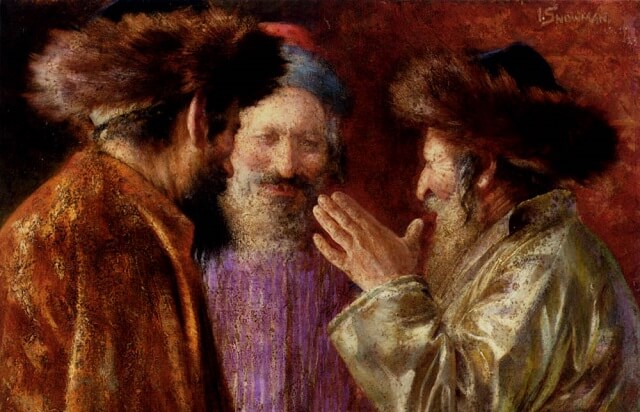

Illustration image: ‘Three Rabbis of Jerusalem’ (Isaac Snowman, 1873-1947)