It is disturbing to see wicked people succeed and prosper. “I envied the arrogant,” the psalmist admits, “when I saw the tranquility of the wicked.”

Despite their deplorable lifestyle, they appear to live their lives without worries. They behave like reckless drivers, endangering others as they weave in and out of traffic, their speeding cars boasting, “No Fear!”

“כִּי אֵין חַרְצֻבּוֹת לְמוֹתָם, וּבָרִיא אוּלָם.”

“There are no pangs (חרצובות) about their death; and their health (אולם) is sound.” (Psalms 73:4)

The meaning of חרצובות is not clear. The Sages explained that it is a composite word, combining the words חרד (to tremble) and עצוב (to grieve).

“Not only do the wicked fail to tremble and grieve regarding the day of death, but their hearts are as steady as an edifice (אולם).” (Shabbat 31b)

Rav Kook noted that the Talmud is enumerating the two factors that usually bring people — unless they are incorrigibly evil — to recognize their spiritual and moral side. The two factors are: (1) contemplating death, and (2) the soul’s innate moral compass and sensitivity.

Reflecting on Death

Those mired in materialistic goals are unaware of the tragic loss when their soul disconnects from its true nature and fails to acquire the traits of holiness it was meant to attain.

Death frees the soul from the body’s fetters and physical cravings. After death, the soul can strive to return to its pristine state; it is painfully aware of its distance from its Source.

When we contemplate death, we are forced to confront the mortality of our bodies and the fleeting nature of worldly pleasures. Those who have lost their way should “tremble and grieve.” They feel the pain of חרצובות.

While they may not fully recognize what they lack, having become alienated from a life of spiritual growth and holiness, they will nonetheless realize that these are life’s most important acquisitions. They will regret failing to work toward life’s most significant accomplishments and greatest satisfactions: refining the soul and strengthening its inner light.

The psalmist is disturbed by the phenomenon of people so enmeshed in evil that they fail to consider the ramifications of death. These complacent people are not bothered by the transient and superficial character of their lives. They experience “no pangs about their death.”

A Feeling Heart

The second wake-up call comes from the inner spirit. Sometimes the soul makes its presence felt, and the heart awakens of its own accord. Those who have neglected their spiritual nature and forsaken the path of integrity will suffer the biting sting of these pangs of conscience.

Yet, some people are so thoroughly immersed in evil that they are immune to these stirrings of emotion. It is as if their hearts are enveloped in a thick layer of fat, preventing them from sensing the needs of others.

Not only do they refuse to consider the implications of death, but “their hearts are as steady as an edifice.” Their hearts are numb and unfeeling, like the concrete slabs of an inert building, oblivious to the harm they cause. With a blind arrogance, they live their self-centered lives without considering the implications of their actions.

To protect us from this ailment of spiritual obtuseness, God provided us with a remedy: the Torah. The Torah and its mitzvot elevate all aspects of life, opening the path to be close to God, to be receptive to holiness, pure thoughts and lofty feelings, to contemplate life and do good. The Torah protects us from wallowing in the mud-pit of materialistic cravings and self-absorption.

“God wanted to purify Israel, so He gave them Torah and commandments in abundance, as it says: ‘God seeks [Israel’s] righteousness, so He made the Torah great and glorious'” (Isaiah 42:21). (Makkot 23b)

(Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. III, 177-178)

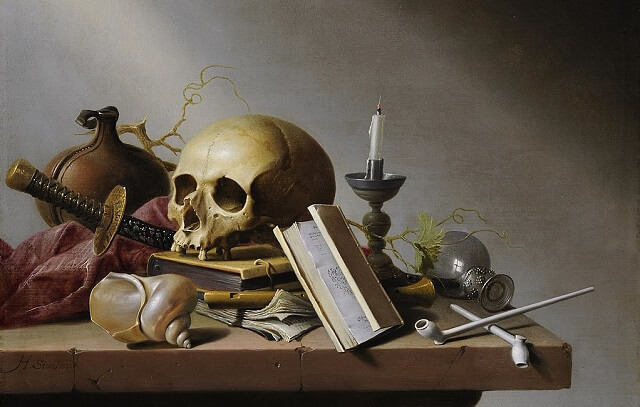

Illustration image: ‘Vanitas’ (Harmen Steenwijck, 1640)