יַעַנְךָ ה’ בְּיוֹם צָרָה, יְשַׂגֶּבְךָ שֵׁם אֱלֹהֵי יַעֲקֹב. (תהילים כ:ב)

May God answer you in a day of distress; may the name of Jacob’s God fortify you (Psalms 20:2).

Why does the psalmist indicate that, in times of trouble, we should call out in “the name of Jacob’s God”?

Why not pray to Abraham’s God, or Isaac’s God?

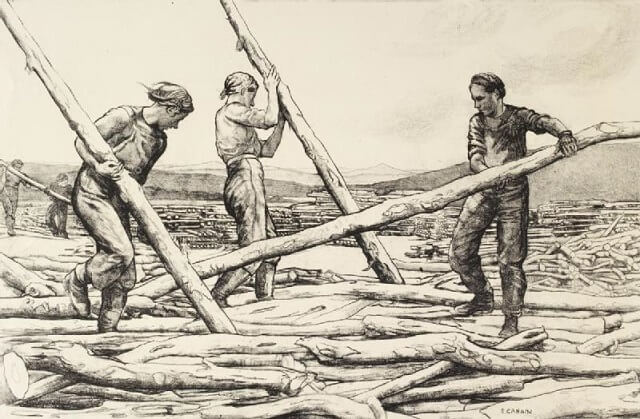

The Sages explained that Jacob is specifically mentioned because “The owner of a beam should grasp the beam by its thickest part” (Berakhot 64a). But this statement is puzzling. What does advice on how to hold an unwieldy piece of wood have to do with prayer in times of trouble?

The Mountain, the Field, and the House

Rav Kook wrote that each of the Avot had his own spiritual path in serving God. Abraham strived to teach the entire world about the One God. The name “Abraham” means “the father of many nations.” His service was embodied by the image of a Mountain. “On God’s Mountain, [God] will be seen.” The Mountain indicates an open, accessible place, inviting all people to approach.

The metaphor for Isaac’s service of God was a Field. “Isaac went out to meditate in the Field.” Like the Mountain, the Field indicates an open place, without boundaries and divisions.

Jacob, on the other hand, heralded the beginning of a new stage in the world’s spiritual development. With Jacob began the establishment of the Jewish people, a nation with a Divine covenant and a holy mission. All of his children formed the twelve tribes of Israel.

This was the start of a new process, the world’s elevation through the influence of a holy nation. Jacob’s service is compared to a House: “the House of Jacob’s God” (Isaiah 2:3). Houses are defined by walls, separating those inside and those outside the structure.

Two Paths

Now we may understand what it means to call out in “the name of Jacob’s God.“

We may draw close to God in two ways. The first path is to approach God through the universal ideals that connect every human soul to its Maker. We may refer to this path as calling in the “name of the God of Abraham and Isaac.” This is a universal path by which all peoples relate to God. It is the Mountain and the Field, the spiritual paths of Abraham and Isaac, accessible to all.

The second path is to call “in the name of Jacob’s God.” This means to base our relationship to God on His special covenant with the Jewish people.

So which path should we take?

The psalmist teaches that during troubled times, we should follow the second path and focus on Israel’s special connection to God. At times of peril and need, it is best to deepen our closeness to God with those aspects that are close to the heart. This approach will inspire an outpouring of the soul and an awareness that we are praying to One Who comes to the aid of those who call out to Him.

By concentrating on this special connection to God — a connection fortified by mitzvot binding us to God’s service — our heart is filled with powerful feelings of love and awe. We are filled with great love for the God of Israel, Who drew us near to serve Him and gave us His Torah.

The universal connection of every human soul to God is a real connection, but it is of a more abstract nature. Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi termed this intellectual service as worshipping “the God of Aristotle.” It lacks the warmth needed to kindle the emotions and gain closeness to God — a sense of connection that is essential in times of trouble. Unlike the more dispassionate intellect, awakening our feelings of love and awe will have a greater impact on our actions, as our emotions are closer to our physical side.

Gripping the Middle of the Beam

Now we may understand the Talmudic metaphor of grasping a wooden beam at its thickest point. A piece of timber has various parts: small branches and twigs at one end, heavy roots at the other. It is easiest to carry a beam by holding it, not at the top, but near the bottom, at its thickest spot.

So, too, one may relate to God with an abstract, universal approach, as the Creator, as the God of Abraham and Isaac. But the psalmist counseled that we grasp, not the upper branches, but the massive trunk. We should hold on to that which is closest to us, that which most directly appeals to our heart and soul. This is “the name of Jacob’s God”: our connection to God as belonging to the Jewish people, as recipients of His Torah.

This advice is especially relevant during times of trouble, whether personal or communal. At such times, we should gather under the flag of the Jewish people, renew our dedication to Torah, and awaken the holy emotions and thoughts that are unique to Israel. With this effort, the national soul of Israel gains strength and power, thus advancing the universal goal of uplifting the entire world.

When the Jewish people will attain a proper material and spiritual state, the time will arrive for Abraham’s blessing. “All of the families on earth will be blessed through you” (Gen. 12:3). But in times of trouble, we should focus on our spiritual heritage. We should firmly grasp the thickest part of the tree, our ties to the God of Jacob. Then we will have a better grip on the branches above — our universal aspirations — as well as the roots below — mitzvot grounded in the physical realm.

(Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. II on Berakhot 64a, sec. 9:356)