Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski (1863-1940), the brilliant Lithuanian scholar and posek, was known to write scholarly Halachic correspondence while simultaneously conversing with a visitor on a totally different subject. When questioned how he accomplished this remarkable feat, Rabbi Grodzinski humbly replied that his talent was not so unusual.

“What, have you never heard of a businessman who mentally plans out his day while reciting the morning prayers?”

Constant Awareness

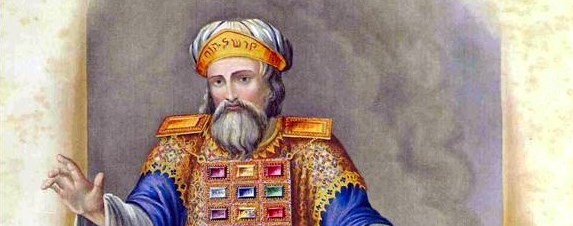

One of the eight special garments worn by the kohen gadol, the high priest, was the tzit. This was a gold plate worn across the forehead, engraved with the words kodesh le-Hashem — “Holy to God.”

The Torah instructs the kohen gadol that the tzitz “will be on his forehead – always” (Ex. 28:38). The Sages understood this requirement not as addressing where the head-plate is worn, but rather how it is worn. It is not enough for the tzitz to be physically on his forehead. It must be always “on his mind.” The kohen gadol must be constantly aware of the tzitz and its succinct message of “Holy to God” while serving in the Temple. His service requires conscious recognition of the purpose of his actions, without irrelevant thoughts and musings. He cannot be like the fellow whose mind was preoccupied with business matters while he mumbled his daily prayers.

Tefillin and the Tzitz

The golden head-plate brings to mind another holy object worn above the forehead: tefillin. In fact, the Sages compared the two. Like the tzitz, wearing tefillin requires one to be always aware of their presence. The Talmud in Shabbat 12a makes the following a fortiori argument: If the tzitz, upon which God’s name is engraved just once, requires constant awareness, then certainly tefillin, containing scrolls in which God’s name is written many times, have the same requirement.

This logic, however, appears flawed. Did the Sages really mean to say that tefillin, worn by any Jew, are holier objects than the sacred head-plate worn only by the high priest when serving in the Temple?

Furthermore, why is it that God’s name is only recorded once on the tzitz, while appearing many times on the scrolls inside tefillin?

Connecting to Our Goals

We may distinguish between two aspects of life: our ultimate goals, and the means by which we attain these goals. It is easy to lose sight of our true goals when we are preoccupied with the ways of achieving them.

Even those who are careful to “stay on track” may lack clarity as to the true purpose of life. The Sages provided a basic rule: “All of your deeds should be for the sake of Heaven”(Avot 2:12). However, knowledge of what God wants us to do in every situation is by no means obvious. Success in discovering the highest goal, in comprehending our purpose in life, and being able to relate all of life’s activities to this central goal — all depend on our wisdom and insight.

For the kohen gadol, everything should relate to the central theme of “Holy to God.” We expect that the individual suitable for such a high office will have attained the level of enlightenment where all of life’s activities revolve around a single ultimate goal. Therefore the tzitz mentions God’s name just once — a single crowning value. Most people, however, do not live on this level of enlightened holiness. We have numerous spiritual goals, such as performing acts of kindness, charity, Torah study, prayer, and acquiring wisdom. By relating our actions to these values, we elevate ourselves and sanctify our lives. For this reason, the scrolls inside tefillin mention God’s name many times, reflecting the various spiritual goals that guide us.

In order to keep life’s ultimate goals in sight, we need concrete reminders. The tzitz and tefillin, both worn on the forehead above the eyes, are meant to help us attain this state of mindfulness.

Now we may understand the logic of comparing these two holy objects. Even the kohen gadol, despite his broad spiritual insight, needed to be constantly aware of the tzitz on his forehead and its fundamental message of kodesh le-Hashem. All the more so an average person, with a variety of goals, must remain conscious of the spiritual message of his tefillin at all times.

(The Splendor of Tefillin. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. III, p. 26)