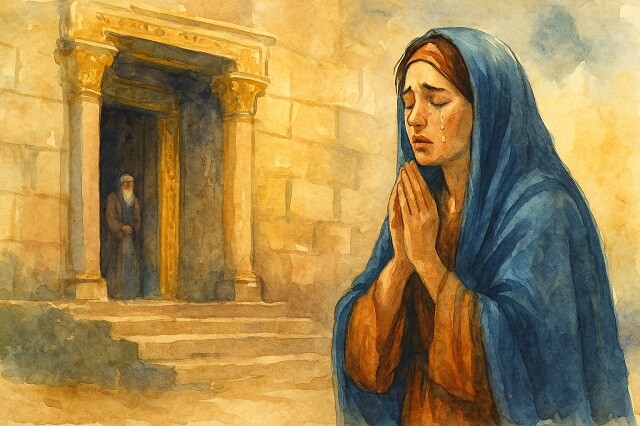

The Suspected Adulteress

The integrity of the family unit is of primary importance in Judaism. For this unit to function properly, the husband-and-wife relationship must be one of trust and constancy. But what happens when this trust, so vital for a healthy marriage, is broken?

The Torah addresses the situation of the Sotah, the suspected adulteress. This tragic case occurs when a woman, previously cautioned by her husband not to seclude herself with a particular man, violates his warning and is seen alone with that man.

The Torah prescribes an unusual ceremony to deal with this potentially explosive situation. The woman is brought to the entrance of the Temple, where she presents an offering of barley meal. The kohen uncovers her hair and administers a special oath. If the suspected adulteress insists on her innocence, the kohen gives her to drink from the Sotah waters.[1] If the wife was unfaithful to her husband, these waters poisoned her. But if she was innocent, the waters did not harm her. In fact, they were beneficial: “she will remain unharmed and will become pregnant” (Num. 5:28).

The Benefit of the Waters

The Sages debated the exact nature of the positive effect of the Sotah waters. Rabbi Yishmael understood the verse literally: if she had been barren, she would become pregnant. Rabbi Akiva, however, disagreed. If that were the case, childless women would purposely seclude themselves with another man and drink the Sotah waters in order to bear children! Rather, Rabbi Akiva explained, the waters would ease the pain of childbirth, or produce healthier babies, or induce multiple births (Berakhot 31a).

Rabbi Akiva had a good point — the law of the Sotah could potentially turn the holy Temple into a fertility clinic. In fact, the Talmud tells us that one famous woman threatened to do just that. Hannah, the barren wife of Elkana, threatened to go through the Sotah process if her prayers for a child went unanswered. (Her prayers were in fact granted, and she became the mother of the prophet Samuel.)

Why was Rabbi Yishmael not troubled by Rabbi Akiva’s concern?

Rav Kook explained that the ritual for suspected adulteresses was so degrading and terrifying, no woman would willingly submit to it — not even a barren woman desperate for children.

Hannah’s Exceptional Yearning

Hannah, however, was a special case. This extraordinary woman foresaw that her child was destined for spiritual greatness. Hannah’s profound yearning for a child went far beyond the natural desire of a barren woman to have children. She was driven by spiritual aspirations greater than her own personal needs and wants.

Hannah was willing to actively demonstrate that her longing for a child surpassed the normal desire of a barren woman. Thus Hannah was ready to undergo the ordeal of the Sotah ceremony. And in the merit of her remarkable yearning, her prayers were miraculously answered.

Only in this unique case was the natural deterrent of the ordeal of the Sotah insufficient.

(Sapphire from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. I, p.135)

[1] Water from the Temple washstand was mixed with earth from the Temple grounds. A bitter root was then soaked in the water. The text of the curse was written on parchment, and the ink was dissolved in the water.