Medical Fees

Amongst the various laws in the parashah of Mishpatim — nearly all of which are of a societal or interpersonal nature — the Torah sets down the laws of compensation for physical damages. When one person injures another, he must compensate the other party with five payments. He must pay for (1) any permanent loss of income due to the injury, (2) embarrassment, (3) pain incurred, (4) loss of income while the victim was recovering, and (5) medical expenses.

This last payment, that he “provide for his complete healing” (Exod. 21:19), i.e., that he cover any medical fees incurred, is of particular interest. The word “to heal” appears 67 times in the Torah, almost always referring to God as the Healer. Only here, as an aside to the topic of damages, does the Torah indicate that we are expected to take active measures to heal ourselves, and not just leave the healing process to nature.

This detail did not escape the keen eyes of the Sages. “From here we see that the Torah gave permission to the doctor to heal” (Berachot 60a).

Yet we need to understand: why should the Torah need to explicitly grant such permission to doctors? If anything, we should expect all medical activity to be highly commended, as doctors ease pain and save lives.

Our Limited Medical Knowledge

The human being is an organic entity. The myriad functions of body and soul are intertwined and interdependent. Which person can claim that he thoroughly understands all of these functions, how they interrelate, and how they interact with the outside world? There is a danger that when we treat a medical problem in one part of the body, we may cause harm to another part. Sometimes the side effects of a particular medical treatment are relatively mild and acceptable. And sometimes the results of treatment may be catastrophic, causing problems far worse than the initial issue.1

One could thus conclude that there may be all sorts of hidden side effects, unknown to the doctor, which are far worse than the ailment we are seeking to cure. Therefore, it would be best to let the body heal on its own, relying on its natural powers of recuperation.

Relying on Available Knowledge

The Torah, however, rejects this view. Such an approach could easily be expanded to include all aspects of life. Any effort on our part to improve our lives, to use science and technology to advance the world, could be rebuffed on the grounds that we lack knowledge of all consequences of the change.

The Sages taught: “The judge can only base his decision on what he is able to see” (Baba Batra 131a). If the judge or doctor or engineer is a competent professional, we rely on his expertise and grasp of all available knowledge to reach the best decision possible. We do not allow concern for unknown factors hinder our efforts to better our lives.

“The progress of human knowledge, and all of the results of human inventions — is all the work of God. These advances make their appearance in the world according to mankind’s needs, in their time and generation.”

(Sapphire from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. I, p. 390)

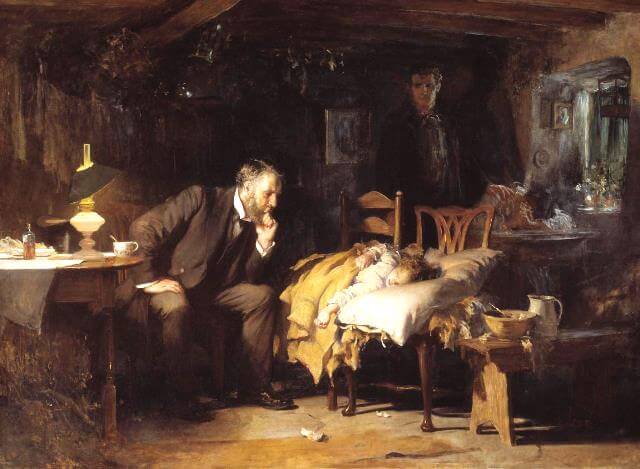

Illustration image: ‘The Doctor’ (Luke Fildes, 1891)

1 The tragic example of birth defects as a result of treating morning sickness in pregnancy with thalidomide comes to mind.