Why Break the Tablets?

“As he approached the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, Moses was angry. He threw down the tablets in his hand, shattering them at the foot of the mountain.” (Ex. 32:19)

Why did Moses need to break the luchot? He could have put them aside for a later time, when the Jewish people would be worthy of them. The Torah does not record that Moses was criticized for destroying the holy tablets. On the contrary, the Talmud teaches that God complemented Moses for this act: “Yashar Kochacha!” “Good job that you broke them” (Shabbat 87a). Why did they have to be broken?

The question becomes stronger when we note the exceptional nature of these unique luchot. They were “the handiwork of God, and the writing was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets” (Ex. 32:16). The second luchot did not possess this extraordinary level of sanctity. When God desired that a second set of tablets be prepared, He commanded Moses, “Carve out two tablets for yourself” (Ex. 34:1), emphasizing that these tablets were to be man-made. Furthermore, unlike the engraved writing of the first luchot, God said, “I will write the words on the tablets” (ibid). The letters were written, not engraved, on the second tablets, like ink on paper. Why were the second luchot made differently?

Beyond Man-Made Morality

The two sets of luchot correspond to two different paths to serve God.

The first path is when we utilize our natural capabilities to live an ethical life. We perform good deeds and acts of kindness out of a natural sense of integrity and morality.

However, God meant for the Jewish people to aspire to a higher level, beyond that which can be attained naturally, beyond the ethical dictates of the intellect. It is not enough to help the needy, for example, because of natural feelings of compassion. This is praiseworthy. But the higher path is to help those in need because through this act one fulfills ratzon Hashem, God’s will.

Ethical deeds that are the product of human nature are like a candle’s feeble light in the bright midday sun , compared to the Divine light that can be gained through these same actions. The loftier path is when the Torah is the light illuminating our soul. We do not follow the Torah because its teachings correspond to our sense of morality, but due to our soul’s complete identification soul with the Torah, which is ratzon Hashem.

The Sages hinted to this level in the Passover Haggadah. “If God had brought us near to Mount Sinai and not given us the Torah, it would be enough [to praise Him].” What was so wonderful about being close to Mount Sinai?

As the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai, and prepared themselves to accept the Torah, God planted in their souls a readiness to fulfill His will. This preparation was similar to the natural inclination of moral individuals to perform acts of kindness.

This explanation sheds light on a difficult verse in Mishlei: “Charity will uplift a nation, but the kindness of the nations is a sin” (Proverbs 14:34). According to the Talmud in Shabbat 146a, “Charity will uplift a nation” — this refers to the Jewish people, while “the kindness of the nations is a sin” — this refers to other nations. What is wrong with the kindness of the nations?

Performing acts of kindness and charity out of a natural sense of compassion is certainly appropriate and proper — for other nations. For the Jewish people, however, such a motivation is considered a “chatat” — it “misses the mark“ (the literal meaning of the word cheit). The path meant for the Jewish people is a higher and loftier one.

Under the Mountain

After receiving the Torah and before the sin of the Golden Calf, the Jewish people were like angelic beings (Psalms 82:6, Shemot Rabbah 32:1). They sensed ratzon Hashem with such clarity that their desire to do good was not based on character traits, but because the light of God and His will that could be found in such acts. Their souls completely identified with the light of Torah.

At that point in time, they deserved the first set of luchot. These tablets were the work of God, just as their own natural inclinations matched God’s will. And the writing was engraved in the tablets themselves, not a separate material like ink on paper. So too, their souls were united and identified with God’s will.

Their state was so elevated, their holiness was so intrinsic, that they were almost at a level beyond sin, like celestial bodies that cannot change their paths. This is the meaning of the Talmudic statement that the Jewish people stood literally “under the mountain” (Ex. 19:17), i.e., that God coerced them to accept the Torah as He raised the mountain over their heads. This metaphor alludes to a state whereby their inner connection to the Torah was so strong that they lacked true free will whether to accept the Torah.

The Golden Calf

But for the Erev Rav, the mixed multitudes of peoples who left Egypt with the Israelites, this service of God was simply too lofty. They aspired only to the regular level of ethical perfection, based on character traits and human intellect. Therefore, the Erev Rav demanded a physical representation of God. They wanted a service of God rooted in that which one can feel and sense, the natural feelings of human compassion and kindness.

Tragically, the Erev Rav succeeded in convincing the Israelites to abandon their lofty level. Even worse, as they relied on their natural sense of morality, they lost even this ethical level due to their undisciplined desires. They descended into a state of complete moral disarray — “Moses saw the people were unrestrained” (Ex. 32:25) — and they transgressed the most serious offenses: idolatry, incest, and murder.

After the Jewish people had abandoned their elevated state, they required a new path of Divine service. But as long as the covenant of the first luchot existed, no other covenant could take its place. Moses realized that they would not be able to return to that lofty state until the end of days. The first luchot needed to be destroyed so that a new covenant could be made.

Interestingly, the Torah notes that Moses destroyed the tablets “under the mountain.” The first luchot belonged to Israel’s unique spiritual state of “under the mountain,” when God’s will was so deeply implanted in their souls that they had little choice but accept the Torah.

The Holy Shekel

The covenant of the second luchot signifies a lower path of serving God, one closer to our natural faculties. Thus the second tablets combined both man-made and heavenly aspects. Moses carved out the stone tablets, but the writing was from God.

God nonetheless desired to leave us with a residual form of the loftier service of the first luchot. For this reason, we have the mitzvah of donating a half-shekel coin to the Temple, thus connecting every Jew with the holy service in the Temple. This donation, the Torah emphasizes, must come from the shekel hakodesh, from the highest motives, for God’s sake alone — “an offering to God” (Ex. 30:13). And the Torah introduces the mitzvah of the half-shekel with the words, “When you will raise the heads of the Israelites” — a hint that it raises up the Jewish people to their once lofty level, when they encamped at Mount Sinai.

(Adapted from Midbar Shur, pp. 298-305)

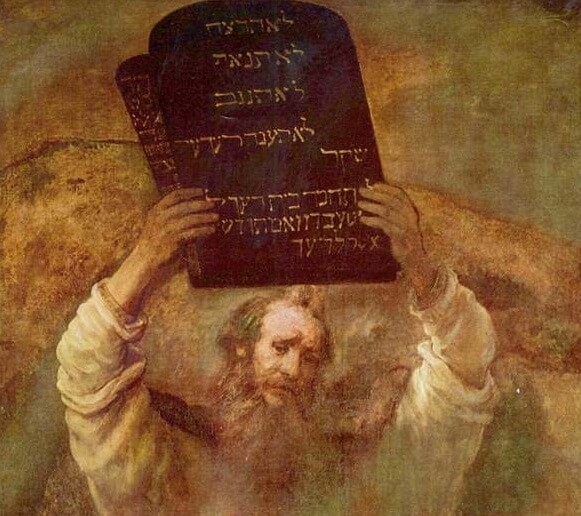

Illustration image: ‘Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law’ (Rembrandt,1659)