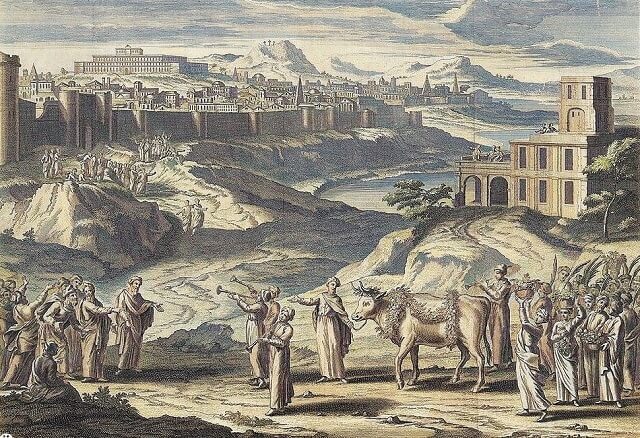

The Mishnah in Bikurim (3:2-3) describes the impressive procession of Jewish farmers as they brought their first-fruits to Jerusalem:

“How were the first-fruits brought up to Jerusalem? Farmers from surrounding towns would gather in the district capital and camp out in the main square. In the morning, the officer would call out, “Let us rise and ascend to Zion, to the House of God!” ... An ox walked in front of the procession, its horns covered with gold and a crown of olive twigs on its head. A flute would be played before them, until they drew near to Jerusalem.”

What was the significance of the ox? Why the golden horns and olive-twig crown? And why was the flute chosen for musical accompaniment?

Labor, Prosperity, and Wisdom

Most nations understand the value of labor and productivity. They strive to create a social framework for honest, productive living. Progressive nations aspire to two additional goals: national wealth and wisdom. Through their prosperity, they are able to enlighten the world with their wisdom and knowledge.

The ox, the classic beast of burden, represents the value that society places on productive labor. The ox walked proudly in front of the farmers who brought their first-fruits — an impressive symbol of their solid, respectable way of life.

The ox’s horns were plated with gold, a sign that, while riches may be acquired in many ways, the most honorable route is through honest, productive labor.

Why was the ox crowned with olive twigs? Olives and olive oil symbolize enlightenment and wisdom. The only oil used in the Temple Menorah, a symbol of light and wisdom, was refined olive oil. Thus the ox’s olive-twig crown indicates that our aspirations should not be limited to labor and wealth. The crowning goal of our efforts should be wisdom.

Why the flute?

Long ago, the flute was played not only at weddings and other happy occasions, but also at funerals. Its mournful notes helped evoke emotions of loss and grief.

The ox, with its gold horns and olive-twig crown, was a metaphor for productive labor, prosperity, and wisdom. Yet, these three measures of success may be used for both good and evil. Hard labor can oppress and darken the human spirit. Wealth can lead to overindulgence in physical pleasures, desensitizing the spiritual faculties of the heart. Knowledge too may be misused for destructive and evil purposes. The flute, a symbol of both joy and sorrow, signified the moral ambiguity inherent in these aspirations.

Yet, if the procession is leading towards Jerusalem — “God’s word will come from Jerusalem” (Isaiah 2:3) — we are confident that these three assets will be used for elevated goals. Then the flute, which may also accompany unhappy occasions, will ring out in joy before them, “until they draw near to Jerusalem.”

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 334-335. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. II, p. 413)