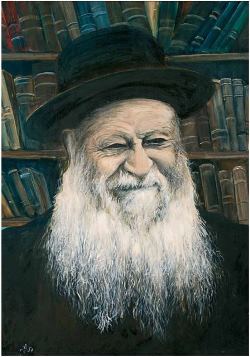

The following account, related by a student of Mercaz HaRav, took place during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The story illustrates Rabbi Zvi Yehudah Kook’s guidance on how we should conduct ourselves during troubled and difficult times.

Yom Kippur that year, I prayed at Beit HaRav, the original location of the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva in Jerusalem. Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook also prayed there. During the chazan’s repetition of the Musaf prayer, we were startled to hear the civil defense alarms wailing throughout Jerusalem.

After Yom Kippur ended, I was called up to my unit. For over a month I was stationed in the Sinai Desert.

When I was finally granted a short leave from the army, I made my way to Jerusalem. First I went to the Kotel, where I prayed, pouring out my heart over the terrible sights I had witnessed during the war. Then I visited my fiancée. Our wedding date had already arrived, but due to the war it had been postponed indefinitely.

My fiancée asked me, “What will be with our wedding?”

I told her that now, in the midst of this dreadful war, with so many soldiers killed, wounded and missing, I didn’t think it was the right time to get married. The situation was still very tense and we were afraid the fighting might break out again. It was impossible to know when and in what condition we would return from the war. Therefore, I explained, we must postpone the wedding until the situation stabilizes.

Reluctantly, my fiancée accepted my decision.

I returned to my unit in Sinai. We dug into our lines and kept a constant lookout for enemy forces. Tensions were high. Henry Kissinger, the American Secretary of Defense, had arrived in Israel, with his shuttle diplomacy between Jerusalem and the Arab capitals. But our worries and fears deepened.

After a few weeks, I was granted a second leave. Once again, my fiancée asked, “What will be with our wedding?” I told her that the situation was still difficult. We have no choice but to wait.

“You have a rabbi,” she said. “Ask him. Seek daat Torah — consult with a Torah scholar.“

I was pleased by her suggestion and immediately made my way to Mercaz HaRav. The yeshiva was nearly empty, as many of the students had been called up for the war.

I met with Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook and related my dilemma. I spoke about the terrible war, about the unfathomable number of casualties and soldiers missing in action, about the palpable dangers we faced against on the front lines. I explained that I felt that, in this difficult time, it was not appropriate to arrange a wedding.

The rabbi listened to me with complete attention, and then he reflected on the matter. After a minute of silence, he said, “We act in accordance with the rules of Halakhah (Jewish law). In Halakhah, one decides according to the principles of rov — the majority of cases — and chazakah — the presumption that pre-exist conditions will persist. The majority of wounded soldiers recover, and the majority of those who go out to battle return.”

Normally, Rav Tzvi Yehudah would conclude with some guidance but leave the ultimate decision to the person seeking advice. This time, however, he finished his words with an unequivocal declaration: “Mazal tov! Congratulations!” Smiling, he shook my hand warmly.

I went back to my fiancée and related the rabbi’s verdict. We set a new date for the wedding. I returned to the army, and news of my upcoming wedding lifted the spirits of the entire battalion. They all rejoiced. Soldiers volunteered days of their army leave — it was called a ‘Day Bank’ — and proudly presented me with a gift of 13 vacation days.

The day before the wedding, I took a flight to Lod airport. I prayed at the Kotel, immersed in a mikveh, and stood under the chupah. Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook attended the wedding, as did a few fellow students from yeshiva and some soldiers on leave.

The joy of the wedding raised everyone’s spirits, infusing them with renewed strength. So it was that, during the very days of that blood-soaked war, when our enemies sought to destroy us, we built our home ke-dat Moshe veYisrael, “according to the laws of Moses and Israel.”

In another incident from the war, involving the burial of one of the rabbi’s beloved students, Rabbi Hanan Porat noted:

“It was clear that our rabbi, in his unique manner, wanted to teach us that the Yom Kippur War — despite the many sacrifices, despite the deep crisis that it created — will not break us. On the contrary, our job is to increase light and engage in matters of the ‘land of the living.'”

(Translated from Mashmia Yeshuah (Harbinger of Redemption) by Simcha Raz and Hilah Volbershtin, pp. 359-360, 363)