וַיֵּצֵא יִצְחָק לָשׂוּחַ בַּשָּׂדֶה לִפְנוֹת עָרֶב

“Isaac went out to meditate (lasu'ach) in the field toward evening.” (Gen. 24:63)

The meaning of the word lasu'ach is unclear, and is the subject of a dispute among the Biblical commentators. The Rashbam (Rabbi Samuel ben Meir, twelfth-century scholar) wrote that it comes from the word si'ach, meaning “plant.” According to this interpretation, Isaac went to oversee his orchards and fields.

His grandfather Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, 1040–1105), on the other hand, explained that lasuach comes from the word sichah, meaning “speech.” Isaac went to meditate in the field, thus establishing the afternoon prayer.

Why doesn’t the Torah use the usual Hebrew word for prayer? And is there a special significance to the fact that Isaac meditated in the afternoon?

The Soul’s Inner Prayer

Rav Kook often expanded concepts beyond the way they are usually understood. Thus, when describing the phenomenon of prayer, he made a startling observation: “The soul is always praying. It constantly seeks to fly away to its Beloved.”

This is certainly an original insight into the essence of prayer. But what about the act of prayer that we are familiar with? According to Rav Kook, what we call “prayer” is only an external expression of this inner prayer of the soul. In order to truly pray, we must be aware of the constant yearnings of the soul.

The word lasu'ach sheds a unique light on the concept of prayer. By using a word that also means “plant,” the Torah is associating the activity of prayer to the natural growth of plants and trees. Through prayer, the soul flowers with new strength; it branches out naturally with inner emotions. These are the natural effects of prayer, just as a tree naturally flowers and sends forth branches.

Why was Isaac’s meditative prayer said in the afternoon?

The hour that is particularly suitable for spiritual growth is the late afternoon, at the end of the working day. At this time of the day, we are able to put aside our mundane worries and concerns, and concentrate on our spiritual aspirations. Then the soul is free to elevate itself and blossom.

(Gold from the Land of Israel pp. 56-57. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. I, p. 109)

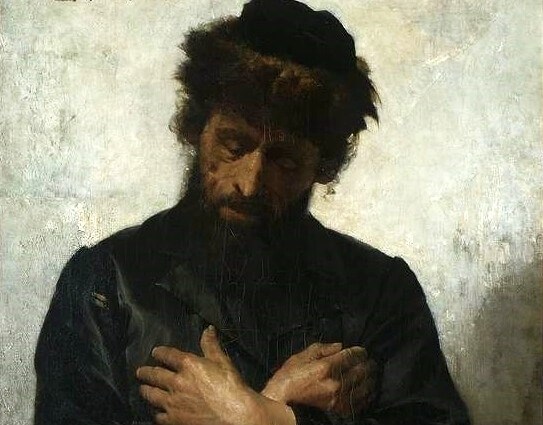

Illustration image: ‘Praying Jew’ (Stanisław Grocholski, 1892)