The Ninth of Tishrei

While there are several rabbinically-ordained fasts throughout the year, only one day of fasting is mentioned in the Torah:

It is a sabbath of sabbaths to you, when you must fast. You must observe this sabbath on the ninth of the month in the evening, from evening until [the next] evening. (Lev. 23:32)

This refers to the fast of Yom Kippur. The verse, however, appears to contain a rather blatant ‘mistake': Yom Kippur falls out on the tenth of Tishrei, not the ninth!

The Talmud in Berakhot 8b explains that the day before Yom Kippur is also part of the atonement process, even though there is no fasting: “This teaches that one who eats and drinks on the ninth is credited as if he fasted on both the ninth and tenth.”

Still, we need to understand: Why is there a mitzvah to eat on the day before Yom Kippur? In what way does this eating count as a day of fasting?

Two Forms of Teshuvah

The theme of Yom Kippur is, of course, teshuvah — repentance, the soul’s return to its natural purity. There are two major aspects to teshuvah. The first is the need to restore the spiritual sensitivity of the soul, dulled by over-indulgence in physical pleasures. This refinement is achieved by temporarily rejecting physical enjoyment, and substituting life’s hectic pace with prayer and reflection. The Torah gave us one day a year, the fast of Yom Kippur, to concentrate exclusively on refining our spirits and redefining our goals.

However, the aim of Judaism is not asceticism. As Maimonides wrote (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Dei'ot 3:1):

One might say, since jealousy, lust and arrogance are bad traits, driving a person out of the world, I shall go to the opposite extreme. I will not eat meat, drink wine, marry, live in a pleasant house, or wear nice clothing... like the idolatrous monks. This is wrong, and it is forbidden to do so. One who follows this path is called a sinner.... Therefore, the Sages instructed that we should only restrict ourselves from that which the Torah forbids.... It is improper to constantly fast.

The second aspect of teshuvah is more practical and down-to-earth. We need to become accustomed to acting properly and avoid the pitfalls of material desires that violate the Torah’s teachings. This type of teshuvah is not attained by fasts and prayer, but by preserving our spiritual integrity while we are involved in worldly matters.

The true goal of Yom Kippur is achieved when we can remain faithful to our spiritual essence while remaining active participants in the physical world. When do we accomplish this aspect of teshuvah? When we eat on the ninth of Tishrei. Then we demonstrate that, despite our occupation with mundane activities, we can remain faithful to the Torah’s values and ideals. Thus, our eating on the day before Yom Kippur is connected to our fasting on Yom Kippur itself. Together, these two days correspond to the two corrective aspects of the teshuvah process.

By preceding the fast with eating and drinking, we ensure that the reflection and spiritual refinement of Yom Kippur are not isolated to that one day, but have an influence on the entire year’s involvement in worldly activities. The inner, meditative teshuvah of the tenth of Tishrei is thus complemented by the practical teshuvah of the ninth.

(Gold from the Land of Israel pp. 210-212. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. I, p. 42.)

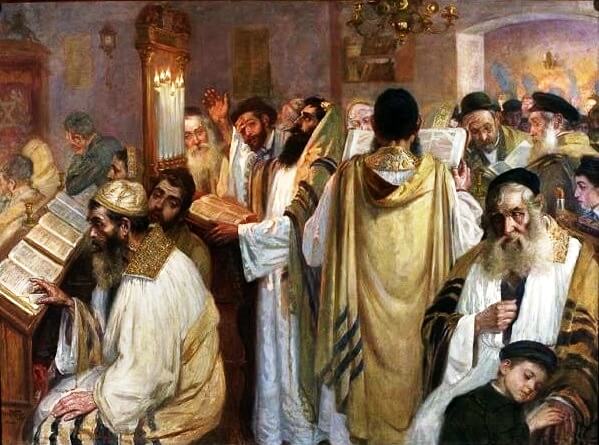

Illustration image: On the eve of Yom Kippur (Prayer), Jakub Weinles (1870-1935)