The Midrash tells the story of how God chose which letter would be the first letter in the Torah. Before the world was created, the letters of the alphabet presented themselves before God. The letter Aleph announced: “I should be used to create the world, since I am the first letter in the alphabet.”

But God replied, “No, I will create the world with the letter Bet, because it is the first letter of the word Brachah (blessing). If only My world will be for a blessing!”

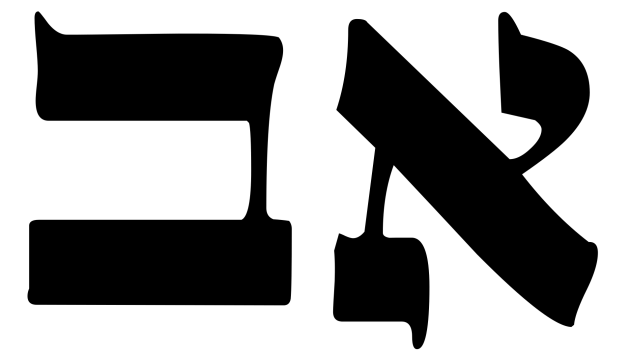

Thus, the account of the world’s creation begins with the letter Bet — Breishit. The Aleph, as the first letter in the alphabet, was given a different honor: it was selected to begin the Ten Commandments, in the word Anochi.

This is a nice story, but what does it matter which letters start Genesis and the Ten Commandments?

Two Types of Light

The creation of light is the source of a major textual difficulty in the Torah’s account of Creation. God created light on the first day, but the sun and the stars were only formed on the fourth day.

So what kind of light was created on Day One?

According to the Sages, the light of the first day was no ordinary light. It was a very elevated light — so elevated that God decided that it was too pure for this world. He secreted this special light away, saved for the righteous in the future. And where did God conceal it? In the Torah.

The Torah, the Sages taught, preceded the world and its physical limitations. The pristine light of the first day also belongs to this initial stage of creation, transcending all limitations of time and place.

Unlike the elevated light of the first day, regular light is produced by the heavenly bodies that were created on the fourth day. Our awareness of the passing of time, of days and seasons and years, comes from the world’s movement and rotation. The sun and the stars, God announced, “will be for signs and festivals, days and years” (Gen.1:14). Our concept of time belongs to the limits of the created universe; it is the product of movement and change, a result of the world’s temporal nature.

The second type of light corresponds to a lower holiness that penetrates and fills the world. In the terminology of the Kabbalists, the higher, transcendent light “surrounds all the worlds” (סובב כל עלמין), while the lower, immanent light descends and “penetrates all of the created worlds” (ממלא כל עלמין).

Now we may understand why the Midrash states that God created the universe with the letter Bet. Bet, the second letter, indicates that our world is based on two forms of infinite light: an elevated, timeless light, and a lower light subject to the limitations of time and place. These two forms of light are the blessing that God bestowed to the world.

Sanctifying the Sabbath

This dual holiness is apparent in the seventh day of creation. “The heavens and the earth and all of their components were finished, and He rested on the seventh day” (Gen. 2:1-2). The holiness of the Sabbath is קביעא וקיימא, set and eternal. It is independent of our actions. And yet, we are commanded to sanctify it: “Remember the Sabbath day to make it holy” (Ex. 20:8). How can we sanctify that which is already holy?

The essential holiness of the Sabbath is eternal, transcending time; but it has the power to sanctify time. By reciting kiddush, we give the Sabbath an additional holiness – the lower, time-bound holiness. Therefore it is written that the Jewish people are blessed with a neshamah yeteirah, an extra soul, on the Sabbath. The first neshamah is the regular soul of the rest of the week, the soul that rules over the body. This soul is bound by the framework of time, just as the body that it governs is temporal and impermanent. On the Sabbath, however, an additional neshamah is revealed: a soul that transcends time, the soul of Israel that is rooted in the highest spiritual realms.

Our recitation of kiddush on Shabbat commemorates two historic events: Creation of the world, and the Exodus. Creation is the aspect of holiness that transcends time, a holiness that is still only potential. The Exodus is the aspect of holiness within time, a holiness that was realized.

Bet and Aleph

Thus the Bet of Breishit is a double blessing: potential holiness and realized holiness; timeless light and time-bound light.

And what about the Aleph? The Torah’s revelation at Sinai came to repair the sin of eating from the Tree of Knowledge. “I created the evil impulse and I created the Torah as a remedy for it” (Kiddushin 30). The Torah reveals the transcendent light of the first day of Creation, the light of timeless holiness. Therefore the first letter of the Ten Commandments, the beginning of the Torah’s revelation, is an Aleph — “Anochi Hashem Elokecha,” “I am the Eternal your God.”

Like the Aleph, representing the number one, the Torah contains the infinite light of Day One, the boundless light that God saved for the righteous.

(Adapted from Shemu'ot HaRe’iyah, Breishit, pp. 6-9 (1931))