Separating from Tzipporah

Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses regarding the dark-skinned woman he had married. (Num. 12:1)

What was Miriam and Aaron’s complaint? The Sages explained that they were upset that Moses had separated from Tzipporah, Jethro’s dark-skinned daughter. Miriam and Aaron were able to receive prophecy without resorting to celibacy. Why did Moses feel he needed to separate from his wife?

The separation was in fact Moses’ idea; God had not commanded him to do this. The Talmud explains that Moses decided it was necessary after he witnessed the Divine revelation at Mount Sinai. Moses reasoned:

The Shechinah spoke with all of Israel only on one occasion, and at a predetermined hour. Nevertheless, the Torah cautioned [the Israelites at Sinai], “Do not go near a woman” Certainly I, with whom the Shechinah speaks at all times and with no set hour, must do the same. (Shabbat 87a)

The Sages noted that Moses’ reasoning was sound and that God approved of his decision. Their proof: after the revelation at Sinai, God told the people, “Return to your tents” [i.e., return to your families]. But to Moses, He said: “You, however, shall stay here with Me” (Deut. 5:27-28).

Why was this separation something that Moses needed to work out for himself? And why was Moses the only prophet who needed to separate from his wife?

Divine Perspective

Despite the innate greatness of the human soul, we

are limited by our personal issues and concerns.

Compared to the Shechinah’s all-encompassing light — a

brilliant light that illuminates

all worlds and everything they contain — our

private lives are like a candle’s feeble light

in the blazing sunlight of the sun. The cosmos

are brimming with holiness, in all of

their minutiae, in their transformations and advances, in their

physical and spiritual paths. All of their heights and depths

are holy; all is God’s treasure.

In order to acquire this higher perspective, a prophet must free himself from his own narrow viewpoint. The pristine dawn of lofty da’at (knowledge) must be guarded from those influences that induce the prophet to withdraw to the private circle of his own family.

Moses, the faithful shepherd, could not be confined to the limited framework of private life, not even momentarily. His entire world was God’s universe, where everything is holy.

It was Moses who recognized the need to separate himself from matters pertaining to his private life. From the Divine perspective, all is holy, and such measures are unnecessary. For Moses, however, it was essential. It allowed him to raise his sights and acquire a more elevated outlook. Separating from his family allowed Moses’ soul to constantly commune with the Soul of all worlds. It enabled Moses to attain his uniquely pure prophetic vision.

Continual Light of Moses’ Vision

What was so special about Moses’ prophecy that, unlike all other prophets, he needed to detach himself from private life?

We may use the analogy of lightning to illustrate the qualitative difference between the prophecy of Moses and that of other prophets.

Imagine walking in a pitch-black world where the only source of light is the light emitted by an occasional bolt of lightning. It would be impossible to truly identify one’s surroundings in such a dark setting. Even if the lightning occurs repeatedly, the lack of constant illumination makes this form of light inadequate. If, however, the lightning is extremely frequent, like a strobe light set to flash at a fast frequency, its illumination is transformed into a source of constant light.

This analogy may be applied to spiritual enlightenment. One cannot truly recognize the elevated realm, its holiness and eternal morality, the rule of justice and the influence of the sublime, without the illumination of continual prophecy.

Ordinary prophecy is like the intermittent light of an occasional lightning bolt. Only the Torah, the unique prophecy of Moses, is a light that radiates continually. We are able to perceive the truth of the world’s inner essence through this constant light, and live our lives accordingly.

(Sapphire from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. IV, p. 174; Orot HaKodesh vol. I, p. 275.)

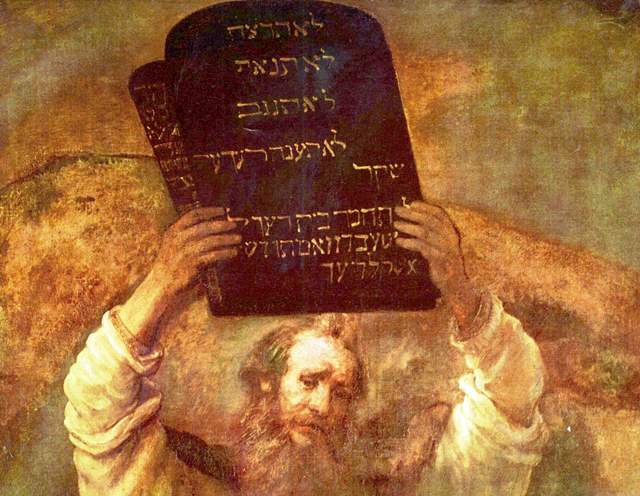

Illustration image: ‘Moses with the Tablets of the Law’ (Rembrandt, 1659)