Ancestral Signs

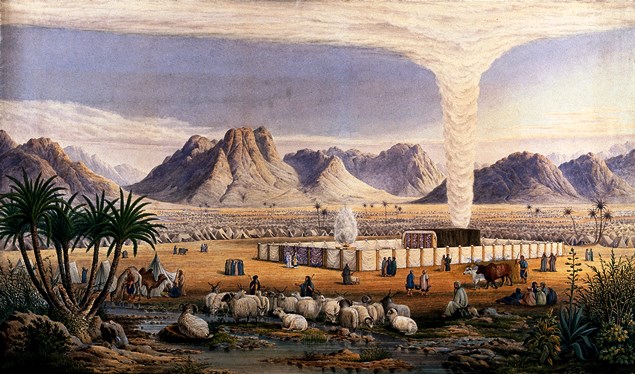

During their sojourn in the Sinai desert, the Jewish people were instructed to encamp according to tribe:

“The Israelites shall encamp with each person near the banner carrying his paternal family’s signs.” (Num. 2:2)

What were these ancestral signs?

The Midrash (Bamidbar Rabbah 2:8) explains that this deployment of twelve tribes surrounding the Tabernacle was in fact a 200-year-old family tradition. Once before, the Jewish people had marched through the wilderness, from Egypt to the Land of Israel. This took place when Jacob died in Egypt. Each of Jacob’s twelve sons took his place around the coffin, as they brought their father to burial in Hebron. Before his death, Jacob informed his sons where each one would stand around his coffin. The arrangement that Jacob established was the “paternal family’s signs” that would later determine the position of each tribe around the Tabernacle, as they traveled in the wilderness.

Why did the tribes need separate encampments? Would not an integrated camp bring about greater national unity? And why was it Jacob who determined the tribal formations in the wilderness?

Jacob and Moses

We find that the Torah is associated with both Jacob and Moses, as it says (Deut. 33:4), “Moses prescribed the Torah to us, an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.” Yet, the relationship of these two great personalities to the Torah was not identical. The Zohar states that Jacob’s connection to the Torah was “from the outside,” while Moses’ connection was “from within.” What does this mean?

In any field of study, there are two ways in which the student connects to the subject material. First, there is the student’s innate interest and aptitude for that particular topic. And secondly, there is the bond that is created through the study of the subject matter.

So too, our relationship to Torah contains two aspects. The first is an innate readiness and inclination to assume the yoke of Torah study. We inherited this readiness to accept the Torah from Jacob — “an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.” Through his profound holiness, Jacob was able to transmit to his descendants a natural receptiveness to Torah.

This quality of the soul is like a pot-handle, enabling us to better grasp the Torah. But when compared to the Torah itself, the soul’s predisposition towards Torah is like an outer garment. Therefore, the Zohar refers to our spiritual inheritance from Jacob as being external — “from the outside.”

Moses, on the other hand, exemplifies a connection to the Torah itself. The Torah is called the “Torah of Moses” (Malachi 3:22). In the formulation of the Zohar, the connection through Moses is internal — “from the inside.”

Uniformity and Plurality

The Torah itself is unified. “There shall be one Torah and one law for you” (Num. 15:16). Within the Torah itself, there are no divisions, no room for divergent paths. The Torah reflects the inner soul, which is indivisible. Thus, in the center of the encampment in the wilderness, there stood a single Communion Tent, a focal point for God’s instructions to His people.

The soul’s natural receptiveness to the Torah, on the other hand, is a function of individual character and personality traits. Here, there exist numerous paths. In these external aspects, in the ways we choose to approach the Torah and fulfill its mitzvot, in the kavanot and intentions by which we focus our minds, it is natural that there will be diversity.

When Jacob’s twelve sons brought their father back to the Land of Israel, each son found his own place around the coffin. Each son positioned himself in accordance to his soul’s natural disposition. Jacob’s holiness imprinted upon each of his children a special connection to the Torah according to his individual nature. That holy procession determined the future arrangement of the tribes of Israel, as they marched to Mount Sinai to receive the Torah. Each tribe had its own special flag and unique place within the encampment of Israel.

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 230-232. Adapted from Midbar Shur, pp. 26-7)