Lengthy Prayers

What makes a great prayer? Are longer prayers more likely to be answered than shorter ones?

The Sages appear to give contradictory counsel. On the one hand, Rabbi Chanina taught that a lengthy prayer will not go unheeded. He learned this from Moses’ extraordinarily long prayer - forty days and forty nights — after the sin of the golden calf. This impassioned plea achieved its goal: “And [God] listened to me also that time” (Deut. 10:11).

Rabbi Yochanan, however, taught the exact opposite! A person who prays at length and “looks into his prayer” — such a person will be disappointed and heartbroken. As it says, “Deferred hope makes the heart sick” (Proverbs 13:12).

The Talmud (Berachot 32b) called attention to this discrepancy. It noted that Rabbi Yochanan specifically spoke of one who “looks into his prayer“ — me'ayein bah. What does this mean?

This phrase is traditionally understood to mean one who looks expectantly for his prayer to be fulfilled (Rashi). Rabbi Yochanan spoke of those who expect that, in merit of their lengthy prayers, they will be answered. Such people, however, are bound for disappointment. Prayers are not automatically answered just because they were recited for a long time. Prayer is not like some automated machine, where, as long as we toss in enough coins, our wishes are automatically granted.

A Time for Prayer and a Time for Inquiry

Rav Kook, however, gave an original explanation to this Talmudic passage. He explained the phrase me'ayein bah literally — that it refers to those who examine and analyze their prayers. During prayer, some people reflect on the mechanics of prayer and its deeper function in the universe. While there is nothing wrong with such intellectual inquiries, it creates a serious problem when it takes place during prayer itself.

Prayer is a natural product of the soul’s inner emotions. It should flow from the depths of the soul’s innermost aspirations. Contemplative thought and analysis are useful as a mental preparation and foundation for prayer. By refining our intellectual understanding and making sure our conduct matches our insights and aspirations, we strengthen the inner soul as it pours out its prayer before its Creator.

But if we combine these calculations and reflections with prayer — during the hour of prayer — that is a mistake. Prayer is not founded on our powers of logic and reason, but on far deeper resources of the soul. Prayer engages the very essence of the soul. It reveals the soul’s inner essence, as it yearns towards the One Who redeems it. When no other mental faculties are admixed with these soul-emotions, then our prayer is purest and most likely to fulfill its purpose.

Rabbi Yochanan spoke of those who pray at length and examine their prayers. Their prayers are lengthy because of their intellectual contemplations during prayer. These individuals will come to heartbreak, for their prayer is no longer the free expression of the soul’s inner emotions. Their prayer contains foreign elements of intellectual analysis and inquiry, and will fail to achieve its true goal.

Preparation for Prayer

Now we may understand Rabbi Yochanan’s remedy for those who have fallen in this trap: to engage in Torah study. How will this help?

Those who seek to deepen their cognitive understanding of prayer should do so — not during prayer, but with Torah study. This intellectual activity should take place before prayer, as a preparation for prayer. And the more we succeed in refining our cognitive understanding, the more our intellect will influence and enlighten the other forces of the soul, the emotions and the imagination.

Those whose prayer is lengthy, not because of reasoned reflections and analyses, but because they strive to bring out the soul’s hidden yearnings and its innate thirst to be close to God — their prayers will be heeded, like the powerful prayers of Moses.

(Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. I, introduction p. 22; Ein Eyah vol. I, p. 150 on Berachot 32b)

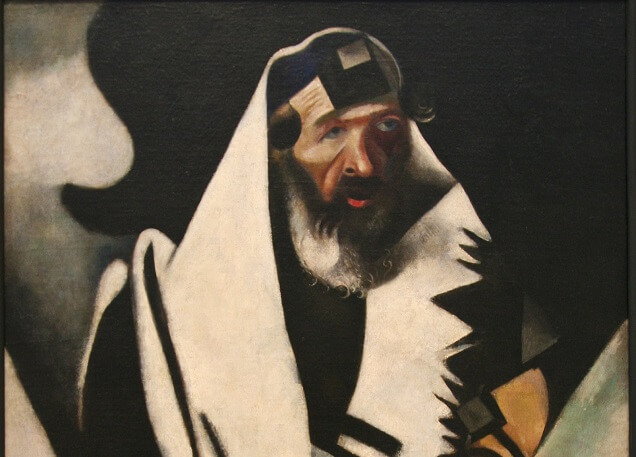

Illustration image: ‘The Praying Jew’ by Marc Chagall, 1923