The central theme of VaYishlach is Jacob’s struggle to find his unique path, especially in relation to his brother Esau.

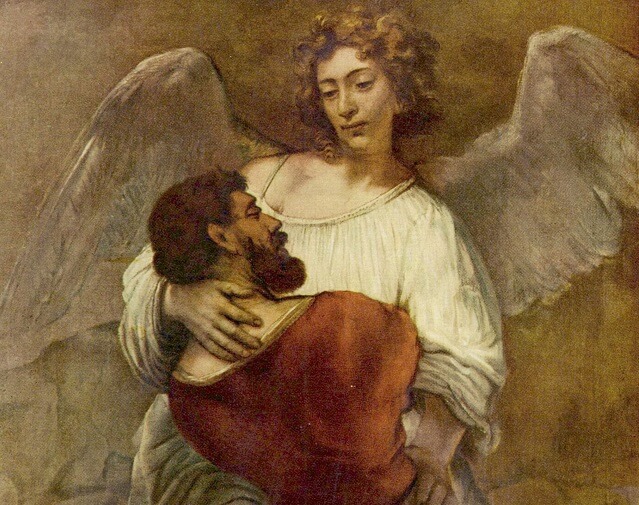

This was not just a family feud. The Sages saw in Esau a symbol for Rome, and more broadly, a non-Jewish worldview alien to the Torah’s outlook. The high point of the narrative unfolds as Jacob engages in a nighttime battle with a mysterious stranger, identified by the Sages as Esau’s guardian angel.

“Jacob remained alone. A stranger wrestled with him until daybreak. When he saw that he could not defeat him, he touched the upper joint of [Jacob’s] thigh. Jacob’s hip joint became dislocated as he wrestled with the stranger.” (Gen. 32:25-26)

What is the significance of this unusual wrestling match? Why did Esau’s angel decide to injure Jacob’s thigh, and not some other part of his body?

Esau’s World of Hedonism

Many years earlier, Esau rejected his birthright, selling it for a bowl of lentil stew. “I am going to die!” he exclaimed. “What good is a birthright to me?” (Gen. 25:32) What motivated Esau to sell his birthright?

We must understand the significance of this ancestral birthright. It was a legacy from their father Isaac, a spiritual charge to lead a life dedicated to serving God. For Esau, holiness is incompatible with a conventional lifestyle. He saw the birthright as a death sentence; it threatened the very foundations of his hedonistic way of life. It was because of this birthright and its responsibilities that Esau felt that he was going to die.

Esau’s viewpoint resurfaces during his reunion with Jacob. When Esau saw Jacob’s family, he was astounded. “Who are these to you?” (Gen. 33:5) You, Jacob, who chose our father’s birthright and its otherworldly holiness — what connection can you have to a normal life? How can you have wives and children?

Esau was unable to reconcile his image of a life dedicated to Divine service with establishing a family and raising children.

In the nocturnal struggle between Jacob and Esau’s guardian angel, the attack on Jacob’s thigh symbolizes this clash of viewpoints. The angel’s message was unmistakable: if Jacob wanted to pursue holiness and devotion to God, he must detach himself from the realm of family and the ordinary aspects of life. The dislocation of the thigh, the source of progeny, signified this separation.

The Elevated Torah of the Patriarchs

Jacob rejected Esau’s views on living a life of holiness. Jacob exemplified, in both outlook and actions, the harmony of nature with holiness. And Jacob’s Torah was revealed in the natural world.

The Midrash teaches that “The Holy One looked into the Torah and created the universe” (Bereishit Rabbah 1:1). This implies that the universe is a result and a manifestation of God’s contemplation of the Torah. If we examine the world carefully, we should be able to uncover the underlying principles of the Torah. If Adam had not sinned, there would have been no need for a written Torah; life itself would be ordered according to the Torah’s principles.

The Patriarchs endeavored to rectify Adam’s sin. Their Torah and mitzvot belonged to the era before the Torah needed to be written down. For them, the Torah was naturally revealed in the universe. This is also the Torah of the angels, whose sole function is to fulfill the mission of their Creator in the world. “Bless God, His angels, mighty in strength, who fulfill His word” (Psalms 103:20).

Who were the messengers that Jacob sent to inform Esau of his arrival? The Midrash interprets the word malachim literally: Jacob sent angels to his brother. A messenger is regarded as an extension of the sender; it is as if the sender himself accomplished the mission. If so, the sender and the messenger must share a connection on some basic level (see Kiddushin 41b).

By utilizing these unusual emissaries, Jacob sent a powerful message to Esau. You, Esau, claim that holiness and physical life are fundamentally contradictory. But my Torah is the Torah of the angels. For me, there is no division between holiness and the natural world. God Himself is revealed within His creation.

(Adapted from Shemuot HaRe’iyah 9, VaYishlach 5630 (1929))

Illustration image: ‘Jacob Wrestling with the Angel’ by Rembrandt (1659)